The Universal Music of Don Cherry

The 20th century was a period of unprecedented, rapid innovation. Nowhere is this more true than in the arts, and within the arts there is no better example than the musics that emerged from African American communities during these years. From the blues and jazz, to R&B, rock & roll, soul, funk, hip hop, and electronic dance musics, no other cultural paradigm created and innovated at such a rapid pace, with such profound impact. As a totality, these musics represent collective and evolutionary body of creativity unlike any other before or since. While none can be regarded as static musics - each, in their own way, continues to give birth to new notions of what they may be - among them, jazz has arguably covered the greatest ground, constantly adapting and reforming into entirely singular and distinct idioms to meet the demands of its moment. Beginning as a street level music of dance and release, it only took a handful of decades to become a music of higher consciousness and profound creative expression; the voice of a people and the greatest indigenous art form that the United States has ever produced. From Jelly Roll on, at the forefront of these innovations are countless well known names; American giants like Billie, Bird, Miles, Trane, Mingus, and Ornette, each taking the music somewhere it had never been, but among them, the roving, soulful mind and voice of Don Cherry arguably pushed the hardest of all.

While far from an obscure figure in the history of jazz, the scope of Don Cherry’s impact - what he actually did - stands slightly aside of its standard narratives. At the center of it all, he was a visionary outlier, relentlessly pursuing his own path, creating a body of music that sounds like nothing else. A universal music. A democratic music, within which a great many peoples, traditions, and histories have a place. His is music that taps the ancient, fundamental human need to express and commune through sound, stretching far beyond the roots from which it sprang.

Born into a musical family, Cherry got his start as pianist, entered the world of jazz while still living in Los Angeles during his teens, joining Art Farmer’s band, before making the leap to trumpet under the mentorship of Clifford Brown. It was only a few short years later, at the tail end of the 1950s, that he made his first significant mark on the history of music, as a member of a central member of Ornette Coleman's legendary quartet; the band that single-handedly set the blue print for the emerging idiom of free jazz. Not only did Cherry contribute to an entire rethinking of what jazz could be, but, even more significantly, the entire potential of music itself.

Laying down the trumpet parts across the near entirety of Coleman's seminal early output, Cherry’s work during this era belongs to the becoming of jazz as truly avant-garde music; a searching music which seeks more honest and democratic means to converse and express, speaking of what is possible within radical dialogical forms. Remarkably it didn’t stop there. During the first half of the '60s, Cherry doubled down as a sideman or under joint bills, producing seminal contributions to the canon of 1960s avant-garde jazz with Sonny Murray, Prince Lasha, Albert Ayler, Steve Lacy, Sonny Rollins, George Russell, François Tusques and Bernard Guérin, John Coltrane, and others, as well as a member of the New York Contemporary 5, co-led with John Tchicai and Archie Shepp, before venturing out on his own as a leader in 1966 and beginning the body of recording that would leave an indelible permeant mark, changing nearly everything in its wake.

While unquestionably brilliant and ambitious, Cherry’s first endeavors as a band leader - Complete Communion and Symphony For Improvisers, both issued on Blue Note in 1966 and 1967 respectively, and 1966’s Togetherness, released by the Italian imprint, Durium - only hint at what was to come. They encounter the trumpet player weaving a complex hybrid of the hard blown avant-garde territories explored with Coleman, and a more restrained temperament of rich tonal and melodic interplay that lays closer to bop.

Though it’s hard to know for sure exactly what, something seems to have happened between 1967 - when Cherry left the United States and moved to Sweden - and the emergence of 1969’s Eternal Rhythm, issued by MPS. His first full length as a leader to appear since Symphony For Improvisers, it roared with life, laying the conceptual and creative foundations for the body of work that took form over roughly the next 13 years; definitive, visionary statements like Mu: First Part / Second Part, Relativity Suite, Orient, Eternal Now, Blue Lake, Brown Rice, Hear & Now, Live In Ankara, and El Corazón.

While displaying little interest in hard technique, Don Cherry was a player of astounding touch and sensitivity, focused almost entirely on where music could go and what it could indicate, express, and emote, continuously followed his ear, bucking the zeitgeist and trends, while making a habit of intervening with himself by performing on instruments that existed beyond own comfort zones, because that was its demand. In all likelihood a genius, the story goes that he could play anything back, note for note, after hearing it only once. These factors, with the historical importance of his early contribution to the foundations of free improvised music, would have certainly assured his place in the narratives, but none are exactly what set Cherry apart. There was something deeper and more ideological in play.

Because Cherry’s music is so singular and distinct, sounding like little else in the canon of jazz, he naturally occupies centre stage in perception, but the heights of these sounds rest within a sublimation of self, giving way to something more whole. Cherry’s music, even when played solo, is a collective music and a social music. It is democratic and hybridic, profoundly human and direct, striping artifice and preconception as it dives toward the heart, drawing countless traditions from across the globe to create a music that stood beyond the locating forces of place, time, or aesthetic constraint. It is a music that channels a love for music, founded on a belief in the profound potential that it holds.

While undeniably prolific, what we have of Cherry's legendary solo work from the 1970s has never quite felt like enough. It leaves you hanging on baited breath, desperate for more. Fortunately, increasingly over the last decade, we’ve been lucky enough to witness a steady stream of incredible live recordings emerge - Modern Art, Live In Stockholm, the incredible calibration with Carlos Ward and Dollar Brand, Universal Silence, issued last year, Live in Frankfurt 82, the mind-blowing LP with Bitter Funeral Beer Band, as well as Baden Baden Free Jazz Meeting December 1967, recorded with Albert Mangelsdorff, Evan Parker, and Marion Brown, and the recent Live At Yubin Chokin Kaikan Hall, Tokyo on May 14, 1986, which encounters him tearing it up with Dave Holland, Steve Lacy, and Masahiko Togashi. Each has offered an incredibly important piece in the puzzle, rendering a far better image of how remarkable Cherry and his music were. Perhaps even more importantly, as great as his studio records are, he’s even better live.

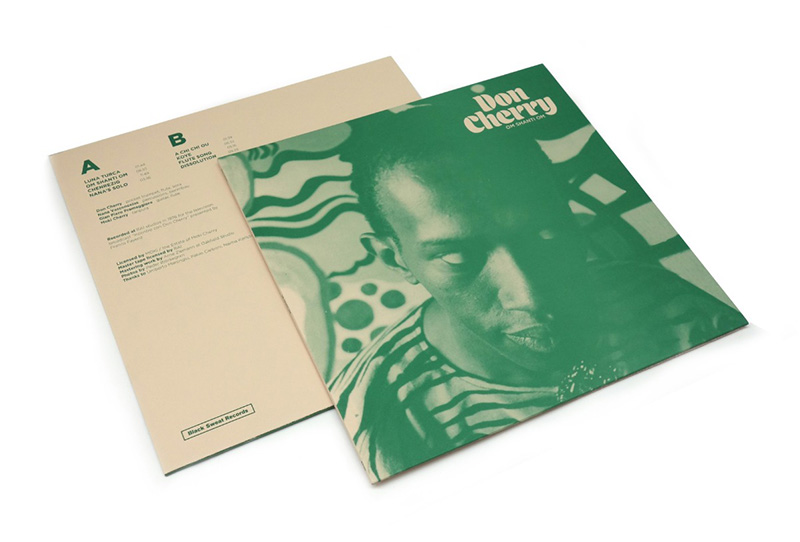

If proof was needed, it’s before us via the always stellar Milan based imprint, Black Sweat, which brings to light a rare body of unreleased archival, recorded by Cherry and his legendary Organic Music Society - in this incarnation, Nana Vasconcelos, Gian Piero Pramaggiore, and Moki Cherry - on Italian TV during 1976. Entitled Om Shanti Shanti Om, it’s easily among the best Cherry records that can be heard.

Recorded in 1976 during a rare Italian television performance, Om Shanti Shanti Om, is Cherry at his absolute best, capturing a pitch perfect image of his roving, restless and ambitious creative mind. There’s little doubt that this an artist pushing into unknown territory, and doing so by looking far afield, drawing on a diverse number of musical traditions; minimalism, Indian Classical and Brazilian traditions, as much as his roots in jazz and blues, reworked and deployed to sculpt an image of an open, universal music of human touch and multidimensional collaboration.

With balance and restraint, across two full sides of material, Cherry's pocket-trumpet melds with Vasconcelos' beats, Gian Piero Pramaggiore's and Moki Cherry's tanpura drone, pushing towards a singular, transnationally influenced hybrid of free jazz and modal, psychedelic jam, before taking detours into worlds of heavy vocal chant and tanpura drones, with the profound elegance of Cherry’s restrained, melodic trumpet lines shimmering overhead, to a killer solo work on berimbau - a Brazilian single-string percussion instrument - played by Nana Vasconcelos, and the deeply moving A chi Chi Ou, reducing music down to its basics with polyrhythmic hand clap and vocals. And then we have Flute Song, making simultaneous nods to southern country blues and Indian classical music with its blend of flute, tanpura, and percussion, each note provoking a recognition of what a profound artist Cherry was.

This is no longer jazz. It is a music that stands outside of place and time. A joyous music that shows a path through our own challenging and difficult moment, offering the means to heal.