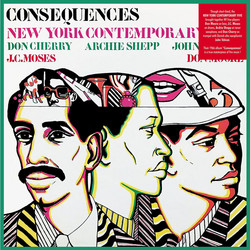

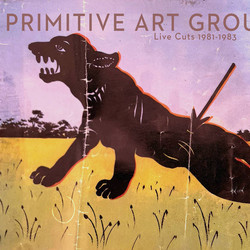

Mega tip! It is well documented that in the early ‘80’s New Zealand was awash with adventurous new music. Though sharing the kind of happy isolation and the DIY ethic with contemporaneous outfits like Flying Nun, South Indies and Xpressway, one band cut a decidedly different path. The Primitive Art Group, formed in Wellington, devoted itself to collective improvisation coming out of a jazz tradition. With the line-up of Anthony Donaldson (drums), David Donaldson (bass), Neil Duncan (saxes), Stuart Porter (saxes), David Watson (guitar), and originally with Pam Grey (on cello), the group’s relatively brief existence left a lasting impression on the New Zealand’s free music scene. Musically, there was no precedent in New Zealand for their combination of noise, collective playing and compositional freedom. Gary Steel from the local music rag TOM, wrote “The first time I saw the Primitive Art Group they blew my tiny mind… Great sheets of architectural noise coming at you from the stage. Where else would you see free music in New Zealand in the early 80s? You just didn't.”

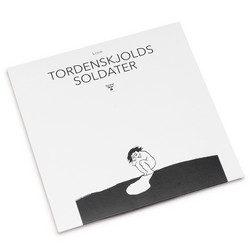

The band’s five-year lifespan was non-stop activity: rehearsing, touring, the creation of Braille Records (their own record label which released ten LPs), dance and theater work, appearances at music festivals, and hosting two hugely influential national festivals of improvisation at Thistle Hall, Wellington. In 1984, Primitive Art Group spent a week making their first recording, an ambitious double LP, Five Tread (Braille 001) which had only a single pressing and sold-out locally. One year later they were back in the studio making their second album, Future Jaw-Clap (Braille 002). This outing contained tighter pieces, as the band widened its repertoire with nods to broader influences and antecedents.

In 1986, The Primitive Art Group gave their last concert at the Wellington Town Hall, just a half mile from Rawa House and the legendary Thistle Hall where their first shows had taken place. The band’s Braille Records’ recordings have never been released outside of New Zealand, nor have ever been available digitally. As Thurston Moore writes, “these are magic time capsule, lost-n-found recordings, previously shared only by deep-diving record collector aesthetes”. The group’s brief tenure has continued to inspire new generations of improvisers, but nothing has ever quite matched the visceral blast of the Primitive Art Group’s arrival on the scene. Every member of the group has carried on doing creative work at the highest levels: scoring films, making art, mentoring, organizing, touring and always playing.