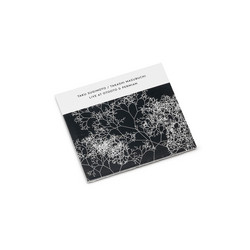

2024 restock. Filmmaker Chantal Akerman presents A Family in Brussels, a fictional stream-of-consciousness text encompassing multiple subjectivities and laced with autobiographical references. This is the first English-language publication of the work, which Chantal Akerman wrote and first performed as a monologue in Paris and Brussels. The accompanying CDs document the theatrical reading that took place at the Dia Center for the Arts, New York, in October 2001. In them, the listener can hear Akerman's singular voice as she muses on familial relations, communication, closeness and distance.

"Akerman’s vision is intimate, rich in emotion and detail. Yet, almost nothing happens. In keeping with much of her previous work, “Selfportrait/Autobiography: a work in progress” is an ode to the lyrical properties of stasis, the secret voluptuousness of flattened affect. While the piece purports to tell a personal story, its true subject is not familial but aesthetic, almost epistemological: Akerman’s focus is the ineffable totality of feeling generated where binary opposites—fiction and reality, voyeurism and opacity, progression and simultaneity—meet and hold each other in perfect tension.

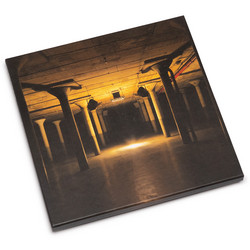

Flickering and murmuring in the dark, the small screen has great votive potential, and Akerman used this quality to full effect. Here, six monitors on plinths were arranged in a graduated triangle—three then two then one—all facing the front of the gallery. Segments of D’Est played on the three monitors in the first row. Back-to- back with these monitors, three chairs faced the other direction, toward the middle two screens, on which segments of Jeanne Dielman played. The final screen-playing selections from two of the director’s lesser-known films, Toute une nuit (1982), and Hotel Monterey (1972)—was framed by the middle two. Directly behind the chairs, a pair of speakers poured Akerman’s voice-over into the viewer’s ear. Thus, to sit in the chairs meant that fully a third of the images went by unseen; to avoid the chairs meant that the story at the heart of the piece could not be heard. Subtly, gently, Akerman forced her audience to make active choices, so that the installation (like history, memory, or prayer) proceeded differently with each participant.

A Family in Brussels recounts the illness and death of Akerman’s father, with the filmmaker speaking, for the most part, in the voice of her mother. We learn that both her parents were Holocaust survivors who settled into a measured, middle- class existence. Akerman appears in the story as the “daughter from Menil-montant,” and at times the “I” of the mother slips seamlessly into the “I” of the daughter; references to “my husband” become “my father” without warning or disruption. These elisions mirror the continuous present of Akerman’s long pans and stationary camera, as if the most radical discontinuity were also the most imperceptible. Just as mother and daughter become antiphonal parts of the same self, the video sequences echo one another as well as the voice-over, so that the young couple in Toute une nuit enters a bar just as Jeanne Dielman ushers in her, afternoon client, and Jeanne Dielman is making coffee or bidding her son good night as the mother A Family in Brussels describes making coffee or visiting her husband on his deathbed.

Akerman speaks in a tranced, mellifluous rush: sentences meld into one another so that buying the morning paper and a relative’s suicide are aligned in an unbroken stream of “and, and, and.” In this tapestry of impressions, the repeated phrase “washed out” becomes a description for the atmosphere—visual, narrative, phenomenological—of the whole. Akerman’s cinematography relies on attenuated movement and muted color; in both D’Est and Jeanne Dielman, these considerations signify the general bleakness of the observed lives. But “washed out” also refers to a spiritual or emotional exhaustion, a distancing of feeling that, paradoxically, becomes vivid again through intent examination. This contradiction functions for Akerman as a kind of meditation, so that while in one respect there is little progression in her work and it doesn’t seem to matter where one tunes in or turns away, in another sense to blink is to miss something crucial, transformative. It is this quality of steady, oblique attunement that makes Akerman’s work so strangely evocative, that softens the relentlessness of her gaze."

—Frances Richard (Artforum)

double CD + book enclosed in a folder