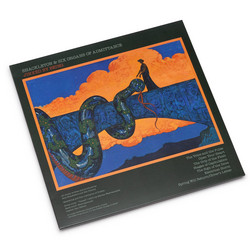

There has never been an album quite like "Axacan", guitarist Daniel Bachman’s latest double LP. By defiantly playing against type and creating an album that, sonically and compositionally speaking, has more in common with Pierre Schaeffer or Edgard Varèse than John Fahey or even Jack Rose, Bachman has crafted one of the most introspective and deeply personal albums of instrumental music released in recent memory. "Axacan" weaves together acoustic guitar and harmonium alongside raw material from various locations, events, and natural phenomena to create a conceptual three-dimensional collage. Using everything from field recordings of church bells, frogs, and birds to treated radio broadcasts, dead pine trees, and tuned fishing wire, Bachman has both honed and mastered the compositional technique hinted at on 2018’s "The Morning Star". As on that album, the guitarist’s approach on "Axacan" is both documentary and authorial, utilizing electroacoustic techniques, organic drones, and environmental sounds to enrich his exhilarating music.

These sounds are deployed reverently; there is very little superficial “sound for sound’s sake” here. Each creak, clatter, or bang colors Bachman’s aural Polaroids with deep and personal significance. The keening and spooky “Blues In The Anthropocene” is a prime example of Bachman’s compositional framework: sounding at first like a lost, ethereal Guitar Roberts side, the piece’s accompaniment by the sound events of rusted tools being throw into a dumpster, high pitched feedback from a radio broadcast, and a storm on Bachman’s familial homestead Ferry Farm—a reputedly haunted plantation and Civil War battlefield once occupied by George Washington—provide a kind of orchestral menace.

The piece ends abruptly, as if the room from which these sounds were emanating was suddenly struck by lightning, leaving only the lonesome sound of rain. “Year of the Rat” begins with a plaintive, unhurried exploration of a guitar tuning, hearkening back to Bachman’s earlier LPs; soon, the playing begins increasing in tempo like a person hurtling deeper and deeper into anxiety recounting a traumatic event before settling down, as if tranquilized. The epic and ominous “Blue Ocean 0” mixes lapping waves, polysynth, fiddle, and tape machine, as well as the sound of wind blowing through fishing line and tuned to a harmonium drone, to convey the grim scientific epoch theorized in its title. “Big Summer,” too, masterfully integrates Bachman’s indisputable guitar prowess with a sense of calamitous menace: the sound of an unaccompanied acoustic slide guitar is heard emanating from what sounds like a waterlogged, malfunctioning cassette, the tremulous vibrato supplied by the limitations of the warbling tape. The effect is like hearing some lost country blues literally unearthed from the soil.

On “WBRP 47.5,” we can make out, amidst radio dial surfing, a brief snippet of dialogue: “…it might be some time before things can…” The voice abruptly cuts off before we can hear more, though we hear this same sample repeated a few minutes later, suggesting that this is less a mere exercise in knob-turning than the evocation of a time loop. The chilly ambiguity of the message, and the accompanying rustling of a dead pine tree slowed to match the pitch of the drone and fiddle, only reinforces the dread. As the radio sounds fade, pained roars evoke immolation, turbulence, the death of a bellowing beast. Bachman follows this with album highlight “Coronach,” a probing 12-string rumination that stands as Bachman’s most accomplished and beautiful guitar piece in years. By carefully selecting and meticulously editing the album’s many extra-and-non-musical sounds, Bachman imbues the music with both a sense of place and a sense of purpose, chronicling a search for meaning, hope, and truth in haystacks both figurative and literal. It is no mean feat to produce a largely instrumental album that somehow deals directly with the crises of our time—climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, the lingering effects of colonialism and genocide—and make it intimate and personal, but "Axacan" is such an album, a spiritual cousin of equally apocalyptic masterpieces like Penderecki’s “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima,” William Basinski’s "Disintegration Loops", and Lou Reed’s "Berlin". Great works of art such as these can often leave you breathless, but they do something else, too: they can leave you changed. - James Toth