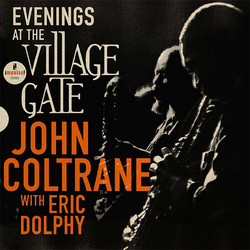

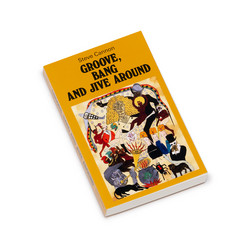

Hardcover, cloth binding, dust jacket The latest work from the veteran novelist called “one hell of a writer” by James Baldwin, “wonderfully wry” by Donald Barthelme, and a “writer’s writer” by Ishmael Reed, Blue in Green narrates one evening in August 1959, when, only eight days after the release of his landmark album Kind of Blue, Miles Davis is assaulted by a member of New York City Police Department outside of Birdland. In the aftermath of Davis’s brief stint in custody, we enter the strained relationship between Davis and the woman he will soon marry, Frances Taylor, whom he has recently pressured into ending her run as a performer on Broadway and retiring from modern dance and ballet altogether. Frances, who is increasingly subject to Davis’s temper—fueled by both his professional envy and substance abuse—reckons with her strict upbringing, and, through a fateful meeting with Lena Horne, the conflicting demands of motherhood and artistic vocation. Meanwhile, blowing off steam from his beating, Miles speeds across Manhattan in his Ferrari. Racing alongside him are recollections of a stony, young John Coltrane, a combative Charlie Parker, and the stilted world of the Black middle class he’s left behind.

Blank Forms’s release of Blue in Green continues the contemporary reenagement with Brown’s work which began with last year’s new McSweeny’s reprint of Tragic Magic, the author’s first novel. Published in 1978 and edited by Toni Morrison, Tragic Magic concerns Melvin Ellington, a man jailed for protesting the Vietnam War; Brown began work on the novel while himself incarcerated on the same charges. In 1992, the author wrote Life During Wartime, a play about the death of street artist Michael Stewart, a victim of police brutality who died in custody. Blue in Green again interrogates detention’s personal, political, and cultural consequences.

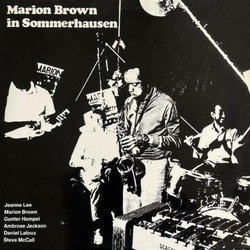

A historical novel much like his 1994 volume Darktown Strutters, the story of a minstrel performer, Blue in Green takes up the voices of a multitude of twentieth-century entertainers at a pivotal moment in American culture and race relations. Staging the conversations of not only Davis, Taylor, Horne, Parker, and Coltrane but also Eartha Kitt, Billie Holiday, and Bill Evans, Brown engages facts to explore relationships between artists of different generations, races, and genders, all of whom must negotiate their positions in what Davis irreverently calls “the business’ known as show.”