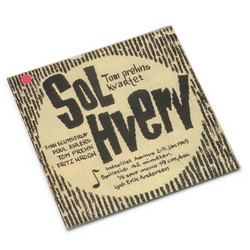

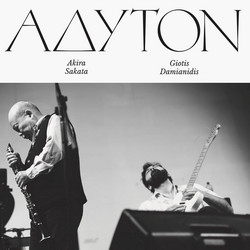

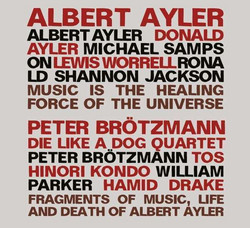

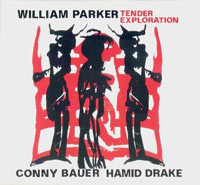

Peter Brötzmann, Toshinori Kondo, William Parker, Hamid Drake

Die Like a Dog

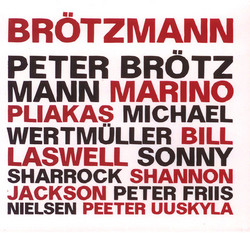

German reedman-composer Peter Brotzmann is, despite an immense catalog spanning over forty years of activity in free music, criminally underrepresented in the format of a "standard" piano-less quartet. From reed-heavy octets and orchestras to the winds-bass-drums power trio, not to mention a long-running trio with percussion and piano, most of the possible formations have been covered. His Die Like A Dog Quartet was the one entry in this instrumental canon in the late 1990s, and produced five records—From Valley to Valley (Eremite, with Roy Campbell, Jr.) and the four discs originally on FMP now collected here. Brotzmann is joined by Japanese trumpeter and master of extended techniques Toshinori Kondo and the now-ubiquitous rhythm team of bassist William Parker and drummer Hamid Drake. The phrase "Die Like A Dog" was initially used in concert with the subtitle, "fragments of music, life and death of Albert Ayler." The first volume is indeed just that, Brotzmann's portrait of Ayler, a figure crucial in the saxophonist's development. Death and mortality figure throughout the discs, with titles such as Little Birds Have Fast Hearts and Aoyama Crows.

Kondo is an extraordinarily curious figure whose electronically-abetted phrases contradict and flesh out the stark phrases of the elder tenor man. Rather than a pitch-divided Ted Daniel or wah-wah Miles, Kondo's shrieks and split tones simultaneously demark and make more ambiguous the literal space that Brotzmann, Parker and Drake occupy and surge through. It's not the same sense of "space" that the music of the AACM or Spontaneous Music Ensemble would bring into the picture, rather something more architectural, an expansion of the group's music into something Edgar Varese, Le Corbusier, and Iannis Xenakis might have found appreciable. And it's a kind of riff on the Ayler ensembles' ability to fill earthly space while playing toward the heavens. Instead of raising the temperature and shaking the rafters of a performance hall, Kondo's electrified trumpet does what Bill Dixon (an avowed influence) might refer to as "making the sound into a cube" and "allowing one to walk inside of it," though not precisely in the same way that Dixon has done—bouncing off walls and creating mutable shapes within the air, it's a strange play on reverberation.

It's interesting to consider Die Like A Dog in the context of a generation of post-Ayler saxophone-led units, especially as players like Brotzmann simultaneously sought to strengthen their foundation as individuals (and Germans or Europeans) and yet also within a free jazz tradition. When critic John Litweiler remarks about Brotzmann's debut inThe Freedom Principle: Jazz after 1958 (Da Capo, 1990), "For Albert Ayler it should have been" and goes on to place For Adolphe Sax (BRO/FMP, 1967) in direct relief to Spiritual Unity, it's a disservice to two saxophonists who were at the time unaware of one another's practice. While fragments of an Ayler call-to-arms weave their way into the title suite of Die Like A Dog and Drake's initial piling, out-of-tempo polyrhythms are comparable to Milford Graves' work on Ayler's Love Cry, it's an homage that quickly begins to occupy other areas.

Kondo builds on Brotzmann's multiphonic wail in crisp, darting punches that at first only slightly pull away from tonality before bends and wows are nearly buried in an electric howl. When his steely blasts emerge, they're in parallel to a sonic-spatial exploration and in concert with tenor bluster, generate a front line that toys with furious overblowing and wry grunginess. Brotzmann's work of the 1970s was especially known for its madcap sensibilities, and though that's certainly less present in this quartet, the presence of Kondo does make for an edgy oddness unlike any of the reedman's other front-line partners.

Rhythm first became a major facet of Brotzmann's groups in the late 1970s, when he began working with the expatriate South African team of bassist Harry Miller and drummer Louis Moholo, a pair whose shared and subdivided swirl buoyed groups like the Brotherhood of Breath and a host of offshoots. William Parker joined the fray at the 1984 Sound Unity Festival in New York, playing in Brotzmann's large ensemble; they reconnected as part of a Cecil Taylor performance at the 1986 Workshop Frieie Musik in Berlin (Olu Iwa, Soul Note). Though he's known for a massive, physical approach to the bow that would have certainly served previous iterations of Brotzmann's music, in Die Like A Dog his role is to permute time and create a fluid, motion-filled chordal-rhythmic underpinning. Hamid Drake joined the group on Parker's recommendation, and while an heir apparent to Moholo and Graves (especially at this early stage), his Africanized approach to free-rhythm percussion also references Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins. He and Parker create some extraordinary time passages that would equally support any down-home blues player, much less one of the doyens of free playing.

The presentation is flawless here; all four volumes are collected neatly under one banner with exhaustive notes reprinted from the original discs. But the music, of course, goes well beyond presentation. Die Like A Dog shows the quartet rightly as a working and cooperative band, one with a shared European, American and Japanese heritage and a sensibility that crosses numerous creative isles with a few fell swoops. Cataloging all the moments contained in this box is pointless, and anyone who feels they have enough Brotzmann in their shelves doesn't without Die Like A Dog in hand.