In a 2007 interview with JazzTimes, trumpeter Eddie Gale spoke about the impetus behind his debut album, Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music, a record so ambitious that not even Blue Note knew what to do with it. It was 1968, and the venerated jazz label was running on the fumes of the hard bop era with swanky, romantic tunes that didn’t address the despair and unrest unfolding outside: a quagmire in Vietnam, the fight for equal rights in the U.S., the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Gale’s album was something else: it conveyed fire, intensity, and most of all, Blackness. “At that point, I didn’t know of anyone who was playing with two drummers and two bassists,” he said. “It just made sense to have this action going on from my love of African music and my time back in the marching band.” Ghetto Music synthesized these touchpoints, honoring the continent’s polyrhythmic arrangements while offering a warm embrace to African Americans fighting bigotry and classism. It was the sound of joy, sorrow, and awakening, funneled through a masterful 41-minute blend of free jazz, meditative soul, and gospel.

Gale’s journey to Ghetto Music began three years prior when the 24-year-old—who had been reared in the bebop stylings of pianist Bud Powell and trumpeter Kenny Dorham—grew fascinated with the burgeoning free jazz movement, a frenetic style that eschewed traditional chord changes for strident improvisation and spiritual connection. By 17, Gale started taking trumpet lessons from Dorham, then started jamming with jazz stalwarts like Max Roach and Art Blakey, all while developing his own style on the horn. This free jazz, dubbed “The New Thing,” confused listeners and critics whose descriptions reeked with elitism. Some fusty jazz critics didn’t want the genre to evolve, and this music—with all its dissonance and ear-piercing shrieks—was far removed from the ’40s and ’50s, where clean-cut performers played smooth melodies in cramped supper clubs.

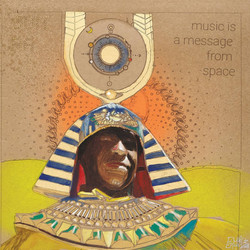

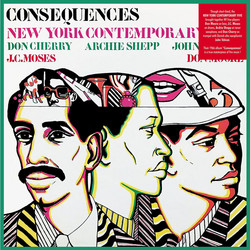

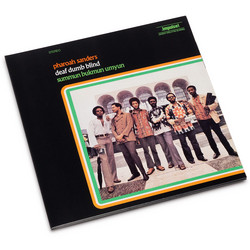

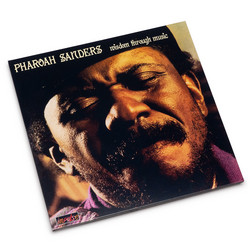

But “The New Thing” was about bringing jazz to people who couldn’t afford expensive tickets and the two-drink minimum. It was from and for communities that needed healing, and evoked the earliest days of the genre when untrained Southern musicians used their instruments to lament discrimination through atonal screeching and wails. In the ’60s, the most famous performer of this new style was John Coltrane, the renowned saxophonist whose 1966 album, Ascension, was far different than the acclaimed, and more melodic A Love Supreme. His embracing of the subgenre brought wider recognition to fellow saxophonists Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, and Archie Shepp, all of whom influenced Gale to find a similar path. He was introduced to Sun Ra in the early ’60s by drummer Scoby Stroman, who was working with the experimental pianist. Gale was soon brought into the Arkestra’s vaunted horn section and played alongside Pat Patrick, John Gilmore, and Marshall Allen, where he learned how to experiment on the trumpet while keeping in the pocket of Sun Ra’s cosmic expanse. In the Arkestra, the bandleader stressed the importance of musical discipline, planting the seeds for the controlled chaos of Ghetto Music.

Gale’s big break came in ’62, when he appeared on “Space Aura,” the third track on Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra’s Secrets of the Sun LP. Three years later, Gale scored a bigger placement when he played on Cecil Taylor’s Unit Structures, the pianist’s first album for Blue Note, now a linchpin record in the annals of free jazz. Then, after a star turn on organist Lee Young’s Of Love and Peace, Blue Note co-founder Francis Wolff asked Gale if he wanted to record his own music. He assembled a sextet that included drummers Thomas Holman and Richard Hackett; bassists Judah Samuel and James “Tokio” Reid; and flutist/tenor saxophonist Russell Lyle; along with an 11-person choir called the Noble Gale Singers. They convened at the famed Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey on September 20, 1968, and recorded Ghetto Music in one day.

The album title itself was an act of rebellion. When people conjure the term “ghetto,” they think poor, dangerous, and Black, coating it in broad, racist strokes. Doing so ignores the community existing there, the togetherness spurred by the dearth of resources afforded to it. Instead, Ghetto Music was meant to celebrate Gale’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn and others like it. “It comes from all of us that lived in that area of the city,” he once said. “That lived this life of music, going to school, learning and growing up. It was all-encompassing.”

Ghetto Music was written as a dramatic presentation accentuated by costumes and acting; between its choral chants and prayerful aura, it was an album that could’ve worked just as well in the Theater District and The East, the famed Black cultural center and venue in Bed-Stuy. Anxious moments were met with equally calm ones, offering a nuanced portrayal of Black life beyond its depiction in the news. Simply put: Black people weren’t taking any more shit from white people; the tenants of nonviolence were giving way to militant-minded retaliation. As the thinking went, brutality would be met in kind; the days of “We Shall Overcome” gave way to James Brown’s “Say It Loud - I’m Black and I’m Proud” and Sly & the Family Stone’s “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey.” Along with that thinking came a new, unflinching pride; the tenor was less about what whites have done wrong and more about looking within for the unification and construction of an isolated Black world.

Where other music jabbed its finger in the chest of the oppressor, Ghetto Music felt like a comforting hug for the oppressed. This is what “The Rain” does when Gale’s sister Joann sings of finding the resilience to move on from distress. “I must leave, so so long,” she coos sweetly, her voice tearful and despondent. “Wipe the tears away from your eyes.” Conversely, “Fulton Street,” a break-neck arrangement with thunderous drum rolls and blistering trumpet wails, is twitchy and nervous, the sense of speeding down the road and beating the yellow signals. The song stops and starts at various intervals, only heightening the intensity; in its silent moments, Gale blasts into his upper register; when followed by cascading drum fills, it’s the sound of a fully pressurized Brooklyn summer day.

Compare that to the mournful “A Understanding,” where Gale plays in a lower register and the choir imparts a slow and solemn tone. It’s as if the weight of injustice has gotten to him and the band, and only the faint recollection of happiness remains. Such thoughts aren’t surprising in this context; riots broke out in the city as a result of King’s assassination in Memphis, along with a student uprising at Columbia University related to the construction of a new gym that residents thought would exacerbate segregation in Harlem. Closer to Gale’s home, a battle over school decentralization in Ocean Hill-Brownsville led to racial tensions over how children were being taught in poorer neighborhoods. Gale funneled these struggles into a singular vision informed by his dismay, though not mired in it. Instead, he used such instances to propel himself and the band forward, blasting into aggressive rhythms rooted in the tenets of Black Nationalism. The instrumental “A Walk with Thee” speaks directly to Gale’s past and present—the marching band student and Sun Ra disciple. Between its military-style ra-ta-tat-tat drums and wistful chanting, it’s a festive jaunt that works equally in open air and at West African nightclubs, the feeling of a crew in lockstep. “The Coming of Gwilu” signals a rebirth, or in this case, the actual birth of Gale’s son, Gwilu. Here, the call-and-response chanting is part of a ritualistic birthing ceremony that, with its 13-minute runtime, comfortably ushers the boy into this world. It lets him know he’s protected from harm.

Gale followed Ghetto Music with Black Rhythm Happening, a 1969 companion album with a nonet and bigger guest features (Coltrane collaborator Elvin Jones played drums and Jimmy Lyons played alto sax) that split the difference between funk and jazz. It refined the edges a bit: While songs like “Mexico Thing,” “Ghetto Summertime” and “Look At Teyonda” (about his daughter of the same name) harbored the raw spirit of Ghetto Music, they landed softer on the ear. Conversely, Gale’s first album encompassed the unrest that threatened his existence, letting it unfold in a billowing haze of combative grooves.

Following the release of Ghetto Music and Black Rhythm Happening, Gale was dropped from Blue Note when co-founders Wolff and Alfred Lion lost control of the label. By the time these albums arrived, jazz had given way to funk as the most popular genre in Black music. Even jazz music’s biggest stars—Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock—had started to blend the genre with psych-rock and funk, which led to an amorphous sound that pushed the sound into bigger venues. Gale’s music was overtly radical; his name didn’t ring as loudly as Pharoah and Ayler in the chronicles of underground free jazz. It seemed the landscape wasn’t ready for a Cecil Taylor-approved, Sun Ra-trained trumpeter who could play straight-ahead and avant-garde in fancy concert halls and on the street. The jazz police couldn’t figure him out, so instead of taking time to dissect Ghetto Music’s dense layers, it was easier to move on to something more palatable. Parts of it were tough to endure if you weren’t of the people, and in an era where jazz was fading from mainstream view, Ghetto Music has mostly gone unappreciated.

Ghetto Music was the genre’s future, and would go on to influence several like-minded bandleaders some 50 years later. You hear traces of Gale in the robust spiritual jazz of Kamasi Washington (who, like Gale, uses multiple drummers and choir) and the jazz-electro-funk hybrid of Damon Locks’ Black Monument Ensemble. And where Gale’s feverish tilt surfaced in Pink Siifu’s 2020 album, NEGRO, Ghetto Music’s inward-looking lament textured Sault’s emotive UNTITLED (Black Is). All these artists employ the same “for us by us” ethos, which, to my ear, closely resembles Gale’s first and best LP as a blueprint for what Black Liberation jazz could sound like. After decades in relative obscurity, Ghetto Music was reissued in 2017 and introduced to a new generation of listeners. “The Rain” and “A Understanding” can be heard in director Shaka King’s Oscar-winning 2021 film, Judas and the Black Messiah, which detailed the plot to kill Black Panther activist Fred Hampton.

In the early ’70s, Gale moved to Palo Alto, California, left the music business, and went into teaching. He continued to perform throughout the years and even appeared on a few noted late ’70s Sun Ra albums (Lanquidity, The Other Side of the Sun, and On Jupiter). Yet nothing else he released had the groundbreaking impact of Ghetto Music—a sweltering and comprehensive masterpiece, a high-water mark for Black love and freedom, a time capsule and summation of 1960s Brooklyn as a beacon of spirit and creativity. All these years later, it still captures the essence of the neighborhood it aimed to serve. “It didn’t sound like anything that came out before or after,” trumpeter Steven Bernstein told The New York Times in the 2020 obituary for Gale, who died that year at the age of 78. “Total outlier. It’s 6/8 vamps with two bass players and two drummers, unison melodies in the horns, and then incredible choirs that are bringing blocks of music.” Indeed, Ghetto Music is still a lightning rod record worthy of deeper study and recognition. With Black life still under siege, this record remains a trek toward inner peace and understanding.