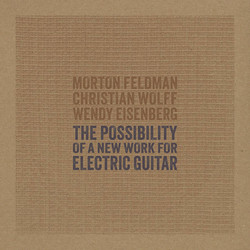

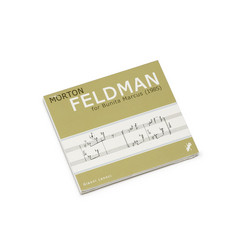

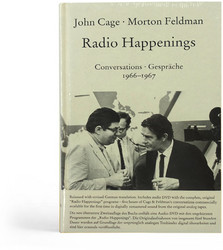

**Original 1985 edition, few copies in stock** Morton Feldman was a big, brusque Jewish guy from Woodside, Queens—the son of a manufacturer of children’s coats. He worked in the family business until he was forty-four years old, and he later became a professor of music at the State University of New York at Buffalo. He died in 1987, at the age of sixty-one. To almost everyone’s surprise but his own, he turned out to be one of the major composers of the twentieth century, a sovereign artist who opened up vast, quiet, agonizingly beautiful worlds of sound. He was also one of the greatest talkers in the recent history of New York City, and there is no better way to introduce him than to let him speak for himself:

Earlier in my life there seemed to be unlimited possibilities, but my mind was closed. Now, years later and with an open mind, possibilities no longer interest me. I seem content to be continually rearranging the same furniture in the same room. My concern at times is nothing more than establishing a series of practical conditions that will enable me to work. For years I said if I could only find a comfortable chair I would rival Mozart. My teacher Stefan Wolpe was a Marxist and he felt my music was too esoteric at the time. And he had his studio on a proletarian street, on Fourteenth Street and Sixth Avenue. . . . He was on the second floor and we were looking out the window, and he said, “What about the man on the street?” At that moment . . . Jackson Pollock was crossing the street. The crazy artist of my generation was crossing the street at that moment. If a man teaches composition in a university, how can he not be a composer? He has worked hard, learned his craft. Ergo, he is a composer. A professional. Like a doctor. But there is that doctor who opens you up, does exactly the right thing, closes you up—and you die. He failed to take the chance that might have saved you. Art is a crucial, dangerous operation we perform on ourselves. Unless we take a chance, we die in art. Just concentrate on not making the lazy move. Polyphony sucks. Because I’m Jewish, I do not identify with, say, Western civilization music. In other words, when Bach gives us a diminished fourth, I cannot respond that the diminished fourth means, O God. . . . What are our morals in music? Our moral in music is nineteenth-century German music, isn’t it? I do think about that, and I do think about the fact that I want to be the first great composer that is Jewish.

These quotations are taken from three collections of Feldman’s writings, lectures, and interviews: “Morton Feldman Essays,” which was published in 1985; “Give My Regards to Eighth Street,” which appeared in 2000; and the new anthology “Morton Feldman Says,” edited by Chris Villars. The books testify to the composer’s rich, compact, egotistical, playful, precise, poetic, and insidiously quotable way with language. The titles of his works make music on their own: “The Viola in My Life,” “Madame Press Died Last Week at Ninety,” “Routine Investigations,” “Coptic Light,” “The King of Denmark,” “I Met Heine on the Rue Fürstenberg.” A champion monologuist, Feldman had an uncanny ability to dominate the most illustrious company. Six feet tall, and weighing nearly three hundred pounds, he was hard to miss. He attended meetings of the Eighth Street Artists’ Club, the headquarters of the Abstract Expressionists; he made his presence felt at gatherings of the New York School of poets, dancers, and painters, lavishing sometimes unwanted attention on the women in the room; he both amused and affronted other composers.

John Adams told me that he once attended a new-music festival in Valencia, California, and stayed at a tacky motel called the Ranch House Inn. When Adams came down for breakfast, he found various leading personalities of late-twentieth-century music, including Steve Reich, Iannis Xenakis, and Milton Babbitt, sitting with Feldman, who proceeded to talk through the entire meal. “A lovable solipsist,” Adams called him. ... (excerpt from Alex Ross)