In recent years, there has been a surge of electronic artists, for the most part new comers, who have rejected the digital approach which had dominated since the nineties in favour of the more organic analogue textures pioneered during the late sixties and well into the seventies by German experimental musicians, from the most exploratory, with the likes of Emeralds or Oneohtrix Point Never, to the bulk of the Scandinavian disco scene, spearheaded by Lindstrøm, Prins Thomas and DiskJokke.

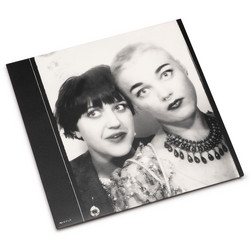

Although hailing from Sweden’s capital city, Stockholm, Roll The Dice have very little to do with the latter, and very much operate within their own realm. Formed of Peder Mannerfelt, who, in recent years, could be found alongside Fever Ray’s Karin Dreijer Andersson, and Malcolm Pardon, Roll The Dice first appeared last year with their self-titled debut album, published on Digitalis, on which they laid out the template for their particular blend of analogue electronic music. Although their sound owed a lot to the kosmische explorations of Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Cluster or Harmonia, Mannerfelt and Pardon tempered that with extensive piano sequences and at times retreated into minimalist sonic forms.

With their second album, published on Leaf, the pair pretty much pick up where they left off, but their opt here for a darker overall tone as they carve stark atmospheric soundscapes, often set in motion by impressive electronic pulses. This is very much the case on Iron Bridge, which opens the festivities. Following a gritty drone build up, the piece is shaken by deep underlying electronic pulses which drag it down into gloomy territories, and, if the softened piano tones occasionally lift the mood later on, this pretty much settles the tone for the rest of the album.

Beside the haunting pulses of the opening piece, Mannerfelt and Pardon inflict some hefty electric shocks into the heady heights of Maelstrom, seemingly wrapping up the ghosts of Brian Eno, Cluster and Vangelis into one easy-to-digest pill, or the more subtle and restrained Way Out, which evolves somewhat more slowly than the tracks surrounding it to spread languorously over the eleven minutes it occupies.

It is perhaps with their more ambient compositions that RtD’s widened scope is the most obvious. While the digital dub on Idle Hands is strangely reminiscent of Pole (Stefan Betke mastered the album), Dark Thirty grows from a spartan two-note piano sequence to a pseudo orchestral behemoth. Cause And Effect also displays some cinematic tendencies as the pair apply a layer of synthetic strings over a gritty electronic loop, while they create much tenser atmospheres later on, punctuated by a recurring bell call on Calling All Workers, or the distracting repetition of a single piano note on The Skull Is Built Into The Tool. On the latter, RtD crank up the unsettling aspect of their music to apply concentrated emotional pressure throughout, until the whole piece disintegrates into a thick sonic paste.

While their debut album had plenty to satisfy, Peder Mannerfelt and Malcolm Pardon have since returned to the drawing board. With In Dust, they have adapted their template to bring more substance to their compositions and as a result, the album is a much more coherent proposition. (theMilkFactory)