A metal fence, about 6 metres high, in the background. A group of people sitting closely aligned on the upper edge, detained by the presence of the border police. A strip of bushy vegetation for sight protection in front of the fence, a bit farther aside some taller palm trees.

An ascending hill behind the fence, dry grass, rock, soil. The well cared for, wavy green of a golf course in the front, two people dressed predominantly in white standing on the lawn, one of them is about to swing the golf club, the other one regarding the events on the other side of the fence. (2)

If an image like this – at least temporarily – draws media attention to fundamental questions of humanity and territoriality in the EU refugee policy, then this photographic scene at the same time also illustrates situational, constitutive moments for localised attributions or links between places and experiences of fear and despair. The profane ordinariness of repeatedly superposed, yet radically diverging perceptions and adoptions of spaces by different social groups and individuals that is displayed in colliding situations, thus describes forms of cooperation, conflict and coexistence in a way that often appears grotesque or absurd, sometimes cynically cold. While such documentations of moments of contingent encounters are sometimes represented in an almost more than obvious way, these observable constellations of alleged exemplary antipodes still have concrete, realistic equivalents beyond medial production or political exploitation. Experience of place and position within locations becomes part of a confusing mixture of localisation and dislocation, which in turn are connected to aestheticised adventure landscapes. Those can be analogies of transitory arrival areas, save shores, touristic functional zones, territory fortified by border barriers, or military operation areas. Space reframed to become a landscape – in individual perception, this transformation hardly ever happens without emotional attachment. From a general perspective or becoming operative in a very subjective way, fear being one possible element of this process percolates both an inner experience and the spaces and places of events. Isn’t it ready to smell, to see, to hear, or to recognise in other ways everywhere “here”?

Knowledge about the spaces of fear, handling danger zones and threat scenarios, continuing vague or concrete alert feeling as an aspect of life, information about one’s self in a state of fear – aren’t there constant comparable appeals and demands in order for us to condition and optimise ourselves in a permanent mode of a “training camp”? Territorial conflict zones, no man’s land, local recreation areas, wellness resorts, safety corridors, wildlife reserves, restricted areas, death zones, no-go areas, gated communities, motion profiles, killing fields, shelter sites, reception camps, coach circuits and Segway tours through “dangerous territory”. In the face of such terms and events, and looking at both individual and social perspectives on addressing space and fear – what is it that forms present, contemporary Landscapes of Fear?

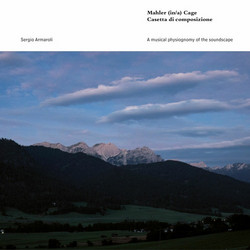

Questions like these, along with Yi-Fu Tuan’s (3) book that provided the title, stood at the inception of the present CD-project that resulted from the seminar series Unsite Temporalities at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne. (4)

The project focused on sound-related aspects and auditive experiential modalities for tracing the current conditions for a political and social exploitation of fear from a spatial (e.g. geographical, territorial as well as topological and auditive) viewpoint, in order to specifically examine the individual, subjective interests of the participants. Acoustic artwork, performances, audio-visual installations, soundscape compositions, radiophonic and documental works were the subjects of analysis and artistic practice alongside productions and material related to trash, horror and science fiction.

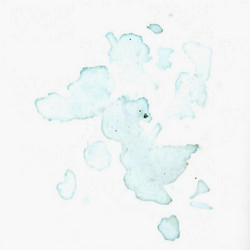

Excursions to places in the wider surroundings of the “Kölner Bucht” that are historically described as “dangerous areas”, “death zones”, “places of fear”, or “restricted areas”, or that are still declared or well-known as such included hands-on field studies and explorations. The overleaf topographic map of the area shows some examples. The map also shows further spatial markings relevant for the project. Temporary localisations and potential zonings are registered in the map along with current political and geographical facts, as well as historic sites; also, some imaginary or medial-fictional spatial positions are marked in addition.

The contributions collected in Landscapes of Fear cover the participants’ different methods and experiences from specifically developed projects on the connection of sound, space and emotion. Multi-layered overlappings of inner and outer spaces, interconnections of forms of acoustic documentation and the phantasms of a sonic fiction, Deep Listening experiments and data analysis – some terms that exemplify the participants’ techniques and subjects taken up during the project. The data of geographical contour lines of existing areas, for example, form the basis for an audification that reads out these topographic profiles as waveforms. Psychological border experiences are set down in text and verbally staged via radiophone. Audio documents (interviews) are tonally processed in a radical way that is based on the spatial model of an existential, physical injury. Urban paths, generated by GPS navigation are translated into an instrumental composition for two stringed instruments. Components and micro particles of verbal communication reveal explosive, controversial potential for aggression within the club and party scene, or coagulate into a stream of intense, yet pale residual sound that causes a “listening deletion” rather than being a basic means of phonetic communication.

The present works reflect a wide range of analysis on the part of the participants regarding the possible manifestations of fear-causing spaces. Among them are detailed observations as well as quite irritating formulations of tonal (landscape-) explorations, acute areas of conflict, commonplace phobias, sonic dissociations and virtual modifications. The works are communicated experiences, aesthetic experiments, tonal speculations and fictionalisations – all of which challenge the positioning of one’s self within an unabated topicality and continuing presence of Landscapes of Fear.

The minimum requirement for security is to establish a boundary, which may be material or conceptual and ritually enforced. Boundaries are everywhere, obiviously so in landscapes of fences, fields and buildings, but equally there in the worlds of primitive peoples. Boundaries exist on different scales. Minimally and perhaps universally, three are recognized: the boundaries of the domain, of the house and of the body. […] Fear is not only objective circumstance but subjective response. […] Landscapes of Fear are not permanent states of mind tied to invariant segments of tangible reality; no atemporal schema can neatly encompass them.“ (5)