“Embryo meets the world” is a new compilation with previously unreleased Embryo's Ethno Jazz from 1979/80, recorded on the German band`s trip to Asia and recently discovered in the archives. It includes seven unknown studio sessions from Kabul, Essaouira, Cairo and Athens, produced with members of the Kabul Radio Orchestra or oud players and singers from Eritrea, Syria and Iraq. Eastern meet Western musicians, improvising with an astonishing deepness over wonderful traditional melodies from Afghanistan, North Africa or the Middle East. All recordings were edited, restored and mastered from the original tapes in 2024. The vinyl LP includes a printed insert with unknown photos and new sleeve notes, the digital album comes with an extensive bonus session, recorded live in Afghanistan.

Reminiscences by Embryo keyboarder Michael Wehmeyer:

By bringing together musicians, film crew, jugglers, actors and visual artists, we started our journey, the long road journey in our bus to India, 1978/79.

The so-called “German jazz pope” Joachim-Ernst Berendt had already organized tours for the Goethe-Institut that took West German jazz musicians to Asia. In the 1960s, this tireless jazz activist produced a series of albums under the title “Jazz Meets The World”, thereby laying the foundations for the new genre of world music in the old Federal Republic of Germany. For his first world music production, Berendt combined Japanese koto players with a jazz ensemble. For us too, the cultural view of the Eastern part of the globe was the focus of our trip. The widespread European view of the U.S.A. at the time, with its high technical standards, had impressed many, but had also triggered a counter-movement in the direction of Asia and other continents that were exotic to us. We embarked on a spiritual quest, out of the narrow continental world of thought, that focused on itself and treated other cultures unsuspectingly or even dismissively.

For us, music was the magnetic field which connected artistic works from different directions. There was a general search for inspiration and everyone tried to be unique and not copy anyone. We looked into the evolution of mankind to find the original forms of artistic developments and their existing power and energy, as far as it had been preserved through living tradition.

Many were on their way to India at the time, some wealthy celebrities had travelled before us and hundreds had brought back stories. Consequently, we too allowed the undiscovered world to flow into our music in order to find something that would broaden our musical horizons and the sound we were used to. Our aim was to create a new fusion of sound. It was the willingness to make a decision and to endure the long journeys to distant lands, to experience a far away destination as an inspiration. The decision and determination whether to make jazz or rock music was pushed off the stage on the way east. We listened to recordings of older jazz musicians with a Far Eastern sound that we sometimes found in private collections or that was mentioned in travel reports. Now it was played right in front of us and after our first impressions in Turkey, this completely new sound finally reached us in the Afghan landscape, in Kabul.

In Afghanistan, we met the first musicians who immediately wanted to play with us. After a few moments of getting to know each other, we were asked when we were going to play together, if not right away. It was a surprising situation, because we were actually unprepared. We hadn't expected brave and curious Afghan musicians, but were happy not to be seen as long-haired tourists or a bunch of hippies looking for meaning.

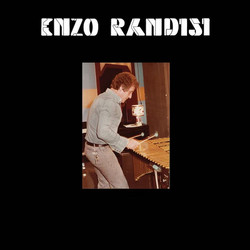

Christian Burchard's vibraphone playing in the Mal Waldron Trio was already praised in the 1960s by the best jazz musicians. He then founded Embryo, because he believed that rock music represented a new basis for improvisation. This approach to playing the rhythms of the world simplified the access to foreign music many times over. The triplet feel of jazz was replaced by the classical binary, rhythmic way of composing. With its simple melodies, Afghan music was rock-like to our ears, but peppered with unfamiliar accents and unexpected twists.

Sounds were still developed without synthesizers. This gave rise to a curiosity for unusual instruments and their possibilities. Roman Bunka, as a rock guitarist and co-creator of the early Embryo music, had therefore experimented with many acoustic stringed instruments such as saz, veena and oud. It was not until we were travelling that the subtleties of the respective cultural way of playing such instruments were really recognized.

The complexity of the supposedly simple music lay in the virtuosity of individual personalities. A very fine sense of rhythm is its prerequisite. Through this realization, we were shown many new ways to play music and to discover and feel the different cultures in their diversity. The unusually delicate rhythms in particular made us curious about foreign sounds. So we were infected and the path to our musical future was paved.

The music of the Kabul Radio Orchestra under the direction of “Ustad” (“Master”) Mohammad Omar with its clear folk melodies challenged our ears. Without knowledge, without the internet, we were catapulted into a new musical world. We got overwhelmed by the enthusiasm of our colleagues from this part of the world. Without shyness and with an intuitive connection, we enjoyed improvising on the basis of a wide variety of traditional compositions. After a sold-out concert in the garden of the Goethe-Institut in Kabul, we agreed to meet again on the return journey from India to Europe.

Back in Kabul, we then had the time to contribute our suggestions six hours a day for three weeks, to learn Afghan music, and to record on 4-track from time to time under the direction of Rolf Sylvester. We subsequently played two big concerts in the city, with folk melodies such as “Anar Anar” (“Pomegranate”), “Bia Bia Janana” (“Come Come My Love”) or “Nastaran”: “The gentle minor and major modal melodies of Nastaran can be seen to depict the up and down aspects of Afghan living”.

We were particularly impressed by the virtuoso zerbaghali playing of Malang Negrabi, who, with his dexterity, managed to set a driving pulse to the simple melodies. A floating groove that allowed the songs to flow through the landscape like an intoxicating river. The Kabul Radio Orchestra played all the jingles and other background music live, not only on the radio but also for one (!) hour of television in the evening, because there were no recording machines available. They waited backstage, so to speak, and were brought into the studio in various groupings. A fascinating process for our technically spoiled lifestyles.

Group lessons were also taught without sheet music so that we could play along. First the richly ornamented melodies had to be simplified for us so that we could slowly understand their exact intonation. At first, everything sounded very similar to us. Time-consuming repetitions then led directly to an overall sound of old and new instruments, a merge of acoustic and electric - world music in its original form and in the framework of an exciting journey of discovery.

Afghan music, which the Radio Orchestra had further developed, was flourishing at that time during a politically tense period in Afghan society. Nobody could predict the future. It was the last intensive cultural exchange in the form of music, because unfortunately there was no further opportunity for joint concerts. When we returned to Kabul, political chaos was already reigning and there was a great uncertainty.

Back in Germany, we used “Farid - die Ursuppe” (a melody by Roman and Christian) as a basic track for our double album “Embryos Reise”, released in 1979. The rock group later recorded additional electric instruments in a German studio over the soundtracks contained here (“Farid Uncovered and Unplugged”!). On the same tape, we also discovered the alternative version of “Anar Anar”, which no one had heard for many years. Inexplicably, a shorter and less virtuoso version of this melody ended up on our album.

After our trip to India, we played with various non-European musicians and sometimes also made sound recordings as part of our tours. The compelling beauty of the local melodies always served as a reason to immediately go into a studio on location. With such unusual repertoire, we wanted to set new impulses in the world music scene. This is how the recently discovered tapes from the Embryo archives with musicians from Eritrea, Syria and Iraq, recorded in Essaouira, Cairo and Athens, were produced.

In Essaouira, Morocco, we had a chance meeting with the oud player and singer Jamal Mohamad from Eritrea. In a recording studio, we improvised over the wonderful Sudanese melody “Win Yannas Habib Roh” by Ahmed Almustafa. Our improvisation of an Eritrean melody, “Eritrean Strut”, was recorded in Cairo, Egypt. Edgar Hofmann's virtuoso flute sounds and the incomparable way in which he plays his soprano saxophone, both hoarse and screaming, lends the tracks an astonishing deepness.

In Athens, Greece, we met the Syrian singer Nissan and Layt Abdoul Ameer, an oud player from Iraq. With Christian Burchard on the santoor, they performed a romantic version of the old Iraqi folk song “Going Out Of Her Father`s House”. “She is going out of her father`s house, going to the neighbor`s house, passed by and did not make Salam...”. Detailed information of this recording session is missing, as well as the great musicians who have left us with their memories over the years.

For over half a century, Embryo have stood for this global and versatile form of musical exchange. The spiritual journey continues.

Recorded 1979 and 1980, all tracks previously unreleased Tracks A1, B1, B2, B3 recorded March 1979 at Goethe-Institut in Kabul, Afghanistan, by Rolf Sylvester Track A2 recorded early 1980 in a studio in Essaouira, Morocco, recording engineer unknown Track A3 recorded early 1980 in a studio in Cairo, Egypt, recording engineer unknown Track B4 is a session recording from Athens, Greece, source and date unknown