Neil Ardley, Ian Carr, Norma Winstone, Barbara Thompson

Mike Taylor Remembered (LP)

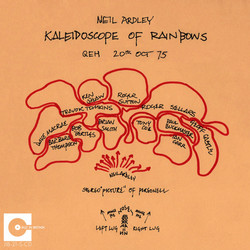

"The Syd Barrett of the avant-jazz scene" - the comparison is inevitable, tragic, and apt. Mike Taylor, British jazz composer, pianist, songwriter, died tragically young, leaving just two albums and co-writes with Ginger Baker for Cream's Wheels of Fire to his name. A talent that burned bright and brief, gone before most people realized what they'd lost. Under the direction of Neil Ardley - himself a significant figure in British jazz composition - several performers who had worked with Taylor gathered to record an album of his surviving orchestral music, jazz tunes, and songs. Not as nostalgic tribute or dutiful memorial, but as urgent act of preservation. This was music that deserved to survive, that needed to be heard, that represented something essential about British jazz at its most ambitious and uncompromising.

Mike Taylor Remembered, taken from Ardley's master tapes, stands as their critically-acclaimed tribute to a master of his art - but more importantly, as a document of Taylor's singular vision. The performers represented a cross-section of the cream of modern British jazz talent of the day, musicians who understood what Taylor had been reaching for, who could inhabit his compositions with the combination of precision and freedom they required. Taylor's music occupied strange territory - too experimental for mainstream jazz audiences, too jazz-rooted for the avant-garde art world, too compositionally sophisticated for rock listeners who knew him only through the Cream connection. He worked in the spaces between categories, creating music that drew on classical modernism, free jazz, English folk traditions, and his own idiosyncratic harmonic language.

Critics who've encountered this album over the decades recognize its importance. As one review noted, this is music that captures "a composer whose work bridged the gap between jazz and contemporary classical music," someone whose "harmonic sophistication and melodic invention" placed him alongside the most forward-thinking British composers of his generation. Another described the album as revealing "the full scope of Taylor's ambition - orchestral pieces that rivaled anything coming from the contemporary classical world, jazz compositions of startling originality." The tragedy of Taylor's story - mental health struggles, creative isolation, early death - shouldn't obscure the achievement preserved here. This isn't music defined by what might have been, but by what actually was: a body of work that pushed British jazz into uncharted territories, that demonstrated how composition and improvisation could coexist without compromise, that proved sophistication and emotional directness weren't opposites.

Ardley's role as curator and conductor matters. He understood Taylor's music from the inside, knew which performers could do it justice, had the technical skill to realize these complex scores while maintaining their spirit. The result is neither sanitized nor overly reverent - it's alive, urgent, emotionally immediate despite the compositional rigor. For anyone interested in British jazz's most ambitious chapter - when composers like Ardley, Michael Garrick, and Graham Collier were creating music that rivaled anything happening in American jazz or European new music - Mike Taylor Remembered provides essential evidence. And for anyone moved by stories of lost geniuses and roads not taken, it offers something more poignant: a glimpse of what was actually achieved before the light went out.