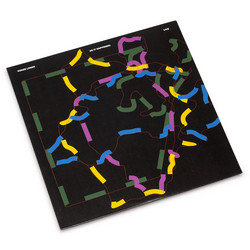

Marc Barreca’s Music Works for Industry is a layered assertion. An economic mantra for the mind to spin, like the many loops on this recording, or churn, as gears of some godhead machine. From the pool of playful compositions, a social subtext appears – a somewhat sardonic riposte to the commercial and cynical abuse of music and musicians. The work profits the listener over industry. Said another way, its motivations are more generative than lucrative.

No longer than four minutes, no shorter than two, each piece on MWFI is a fragment of modern life. Propaganda transmitted between the click of the remote or the turn of the dial. Friend and collaborator K. Leimer checks Cluster, Steve Reich, Iannis Xenakis, and Morton Subotnick as esoteric influences on MWFI in the album’s liner notes, while one might imagine Upton Sinclair, Studs Terkel, or Chris Anderson as egalitarian influences.

Made with musicians, performance artists, and a bespoke instrument maker, Barreca combines multiple disciplines into a collective, industrious whole. An experiment fabricated in the synth and tape studio at the artist-run alternative space and/or (Seattle’s version of NYC’s The Kitchen), Barreca manipulates dynamic sound sources into tidy, minimal arrangements using synthesizers, modified instruments, tape looped voices, and melodic, metallic phrases.

To start, “Community Life” strews these elements across the assembly line to meet their maker. The album continues with “Shopping,” countering ominous, mechanical sounds with light, playful tones, perhaps representative of the clash of production versus exchange values. On “Hotcake” we hear men’s voices, chains, and hissing steam in a methodical but urgent progression that could soundtrack Fritz Lang’s silent film, Metropolis. A woman seductively intones “Nerve Roots Are Uncontrollable” on the track of the same name. “Organized Labor” also incorporates a voice, speaking the acronym I.W.W. – International Workers of the World, also known as the Wobblies – as the music falls in line and wobbles along.

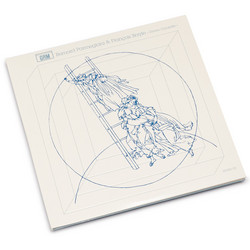

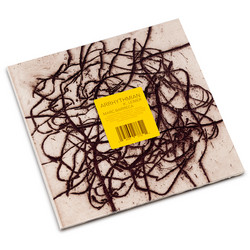

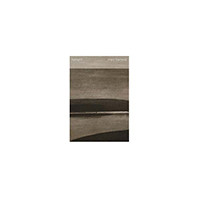

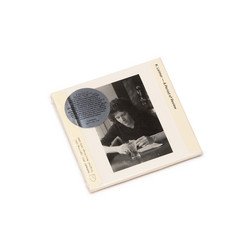

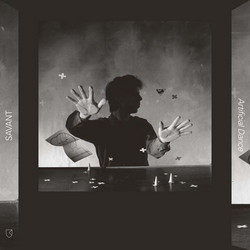

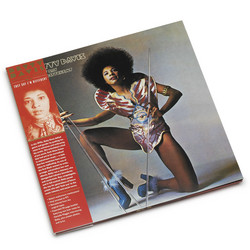

The cover of MWFI features a black and white photo of a figure in silhouette, backlit at a window, softened with curtains and plants. Maybe this is the room where the music was made: a private space, a refuge from some industrial work or at least the dubious fruits of this labor. In a way, listening to the music is entering a space without work, an apple to pluck and eat without wage or taxation.

One can imagine photographer Chauncey Hare listening to Music Works for Industry as he moved from documenting domestic interiors to the bleek efficiency of American offices. His black and white portraits of workers, isolated and obscured by cubicles and files, and published in This Was Corporate America, led to Hare’s disillusionment with the art market. Not wanting to sell images, he left photography, and become a therapist: publishing the self-help book, Work Abuse.

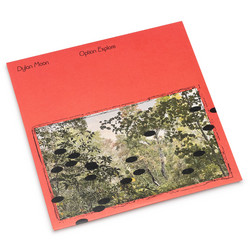

Perhaps peering into the music industry led to Barreca’s eventual career, and a similar impulse to more directly touch those at the effects of economic systems. While exploring the cassette version of Music Works For Industry, we found a business card tucked inside: Marc Barreca—bankruptcy judge in Seattle. Material traces of the cassette are evident in the record’s packaging, the album format a newly manufactured form for Barreca’s work.

Even in post-industrial times, Barreca’s music offers listeners easily consumable musings on current work conditions. Freedom To Spend accepts your hard-earned and fortuitously won money in exchange for these morsels, but also believes that you need not invest unless pressed.