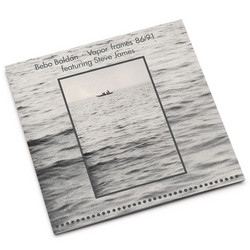

Various

Señales De Síntesis - Música Electroacústica Peruana

In the bulletin 103 of the Casa de las Americas, published in the second semester of 1984, there is an article by Peruvian composer and musicologist Aurelio Tello, offering a full-scale view of what by then was the last generation of Peruvian composers: the generation of the 70s, nicknamed by Celso Garrido-Lecca as “The Superstars”. Making a recap of the musical production of those composers, Tello indicates: “Signs of the conditions under which we work can be seen at first sight: the reduced amount of instruments, null access to contemporary technology, the activity being limited to the National School of Music, just one concert a year, the preparing of pieces in hours outside of everyday activities, etc.”. This comment gives us a first glimpse to the status quo in Perú by the beginnings of the 80s. Let’s go, for a moment, a little further back.

The two composers that had been in the spotlight as far as creation with electronic means in the 60s and 70s were Cesar Bolaños and Edgar Valcarcel. Both composed abroad: Bolaños in Argentina, at the Laboratorio de Música Electrónica of the Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM) of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, while Valcarcel worked at the laboratory of the University of Columbia in the United States of America in the 60s and at McGill University in Canada in the 70s. Bolaños came back to Peru in 1973 and dedicated himself to musicological research thanks to a post offered by the newly founded Instituto Nacional de Cultura. He wrote a couple of instrumental pieces and by the late 70s he practically decided to abandon composition. Nevertheless he dedicated himself fully to studying pre Hispanic musical instruments. On the other hand Valcarcel saw his intent of creating an electronic music laboratory at the Universidad de Ingenieria upon his return to Lima in 1967 fall apart. He returned to Canada by the late 70s and came back to Peru with two more electronic pieces. In conclusion, what both composers learnt abroad had no support in Lima; nevertheless they gave some conferences and premiered their pieces stimulating a younger generation. Even though the dream of a laboratory was not fulfilled there were those who ran some private experiences. Rafael Junchaya Gomez wrote by the end of the 60s an electronic piece as the background for a theatre play using an open reel tape recorder and an assorted set of percussion instruments. Alejandro Nuñez Allauca wrote two concrete pieces using open reel tape recorders in the 60s, before he won a scholarship for the Instituto Di Tella, where he would also write an electro acoustic piece. Pedro Seiji Asato wrote in 1972 a combined piece using radio recordings. And Luis David Aguilar composed instrumental pieces from the late 70s well into the 80s, for two documentary films by Jose Antonio Portugal with a well cared post production treatment, becoming a pioneer in the country as he made the best use of the resources and studio effects for the recording of an avant-garde piece. With a synthesizer he also composed two experiments of nueva cancion, with an underlying totally electronic base. Let’s not forget the works that nearly secretively percussionist Manongo Mujica was undertaking, locked up in a recording studio as he wrote a series of pieces for recording tape, amongst them some used for the short experimental videos by artist Rafael Hastings. Nor the case of Miguel Flores, who had been the drummer for Pax and who, after forming the neo folklore group Ave Acustica in 1974, began the research that took him, already in the 80s, to fuse Andean music, shamanic chants with electronic sounds and extended use of instruments. These pieces were used for the sound track of a performance by choreographer Luciana Proaño.

On the other hand, the diaspora was, as always, the only option to develop for the electro acoustic composer in Peru in those years (even today). By the end of the 70s two composers left Peru to study electronic music: Claudia Woll moved to South University, California and Arturo Ruiz del Pozo went to the Royal College at the University of London and it is Ruiz del Pozo’s work that sets the pace to begin to weave the historical thread of electro acoustic music of the 80s in Peru.

In London Ruiz del Pozo graduated with a series of concrete pieces, using recordings of native instruments, making use of all of the available sound resources that these gave, including rubbing and banging. He called these pieces Composiciones Nativas. He came back to Peru and alongside Manongo Mujica and Omar Aramayo he formed an experimental group called Nocturno, he published Composiciones Nativas independently as a cassette tape and produced a series of concerts in which, besides music, basically being played from the original recording tape sources, he included light projections with water, oil and tints in the best manner of psychedelic projections for San Francisco rock bands. One of these concerts took place at the Auditorio del Banco Central de Reserva in August 1984. The Puno born composer and musicologist Americo Valencia (3) was there and a few days later he published in a newspaper called La Republica these lines:

“In spite of its name and the announced use of native instruments, these have been used to obtain primary sounds for the electronic process, the random-electronic-concrete experimental music we here talk about has no socio cultural backing within the process of Peruvian music in general, much less, in the development of Andean music. Thus, this experimental music has nothing to do with the real experimental music coming from the Andes”.

Valencia’s commentary got itself an answer from the musical critic Roberto Miro Quezada (a jazz connoisseur) generating a debate which gave as a result the publishing of five interesting articles that synthesized the tensions that already in the 70s seemed to direct some of the paths for Peruvian music, on one hand that nationalism which rejected “imported fashions” and, on the other hand, a little bit behind, the interest of some to open themselves to sound experimentation and unorthodox fusion. Roberto Miro Quezada would answer Valencia:

“Why do you feel uncomfortable with the fact that Arturo Ruiz del Pozo is inspired by Andean sounds? I have not talked with Ruiz of this matter – I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting him – but I do not think he is attributing himself the exclusiveness of experimental Andean music. Moreover I do not think Arturo Ruiz thinks he is doing Andean music. As an individual born in these lands called Peru, he is inspired by one of the cultural elements upon which it is conformed.”

To understand the cultural environment in which new composers shall emerge we must go back again to the 70s. As we already know, the coming to power of General Juan Velasco Alvarado in 1968, as head of a military junta which toppled President Fernando Belaunde Terry; provoked a transformation in the cultural imaginary of the country, re positioning folklore and native cultural manifestations as signs of the end of an oligarchy which had been in control of the country. The National Prize for Culture in Fine Arts was handed out to altarpiece artisan Joaquin Lopez Antay, an Ayacucho native. And what is most important, Peruvian composer Celso Garrido-Lecca, founded in 1974 the Talleres de la Cancion Popular, inspired on his experience with left wing groups and the Nueva Cancion in Chile, a country where he lived for 25 years, until his return to Peru in 1973. He also promoted the teaching of native instruments at the National Conservatory and in general he energized Peruvian music with a proposal to look back “into its roots”. Thus an important number of reckoned folk groups were formed. Nueva Cancion had an important place in the cultural life of Lima and its highlight was the creation, in 1986, of the Semana de Integración Cultural Latinoamericana, sponsored by Alan Garcia’s government. Many Latinamerican stars came for that festival which had an astronomical disbursement to cover production costs. Peruvian composer Enrique Iturriaga, from the National Conservatory, indicated then that such an event was taking place turning our backs on reality. (4)

Celso Garrido-Lecca indicated “we have to look at ourselves”. In the meantime Valcarcel had to carry as a burden the fact of being accused of being a pro imperialist musician because he promoted avant-garde music. With the return of democracy in 1980 Valcarcel took the post of head of the conservatory and the Talleres de la Nueva Cancion came to an end.

Our point is that these tensions allow us to shed light on two ideological visions. And that is what we can still see in the discussion between Americo Valencia and Roberto Miro Quezada.

Pay attention to your time

One year after the controversy, in 1985, Americo Valencia traveled to the United States for a post graduate course in electronic music. He acquired some equipment but his interest in more inclined toward research on Andean instruments, especially sikuris. His name was again mentioned in 1988 when he founded the Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo de la Música Peruana (CIDEMP) with Jose Sosaya, another composer.

Sosaya came from Trujillo and he arrived in Lima in the 70s to become an outstanding student at the conservatory. In 1984 he traveled to France for two years for a course in electronic music with the Groupe de Recherches Musicales de Paris and another course at the Conservatorio de Bologna. When he returned to Lima, Sosaya gave some conferences but he had to wait until 1990 to get a synthesizer and a computer to be able to compose his electronic pieces.

Before traveling, Sosaya had met another composer, Gilles Mercier, who also traveled to France to enroll himself at the conservatory in Lyon. Mercier had already begun electronic experimentation taking part in the creation of the sound track of a documentary produced in 1983. When he returned from Paris in 1989 he continued his experimentation using tape recorders, forming the improvisation group Codice with which he performed only once.

With CIDEMP Sosaya gave two concerts in 1990: Escuche su siglo and Musica peruana contemporanea. In both concerts Gilles Mercier presented electronic pieces while Sosaya only presented pieces for instruments. The piece Arp 2600 by Gilles Mercier was the result of a course which the composer took in Sao Paulo that same year. Two years later, he also composed Metamorfosis, one of his best known pieces for cello and synthesizer.

Two other composers from the conservatory would join Sosaya and Mercier: Edgardo Plasencia, who had traveled to Vienna to study electronic composition in 1988 and Rafael Junchaya, Jose Sosaya’s pupil. The four composers produced a concert on December 5th 1991 at Teatro Larco in Miraflores under the name Música Electroacústica Peruana, síntesis digital y MIDI. The concert which was also organized by CIDEMP took place thanks to an initiative by Grupo de Investigacion Teatral, Umbral, lead by the renowned actor and director Alberto Isola. Probably this was the first concert in Peru wholly dedicated to electro acoustic music. It was promoted as the “first MIDI concert of Peruvian compositions”. All in all four pieces were played, amongst them Variaciones sobre un sonido, which Plasencia had composed that same year at the studio of the Hochschule für Musik in Vienna. This was the first Peruvian MIDI piece and it utilized the sound of a charango as its primary sound matter, using a computer controlled Akai sampler. Piedra del Qosqo, by Rafael Junchaya, which was written for two synthesizers and computer, using a CZ-3000, a D-10 Roland and a 1040ST Atari, was also played on that occasion; it also being his first electronic piece. (5)

This group of composers was already creating an imaginary or a new culture based on electro acoustic composition, even though precariously and with the little resources they had. The relationship between technology and art in Lima hadn’t been neither intense nor visible, despite the existence of the Natiotal Council for Science and Technology (Concytec) which gave great support to culture, above all research in its many forms.

It must be said that, coinciding with the production of this MIDI concert, other experiences were simultaneously occurring. For example, the appearance of the noise artist Alvaro Portales and his project Distorsion Desequilibrada who played Industrial Noise, Manifest 1. Months prior to the MIDI concert of Peruvian pieces, the concert Sintomas del Techno, many techno music bands, who had keyboards and synthesizers, joined forces and made themselves known, at La Cabaña. Something was going on. Peru entered uncertain times after President Alberto Fujimori’s self coup. At the same time the country was recovering from its cultural isolation and the hyperinflation it had undergone during the 80s. A consumerism culture was sprouting as Peru moved into a neo liberal economy and opened to foreign capital. Investment, and the consequent consumerism; were directed at the private realm essentially and this was connected to some technological emergence.

By 1993 the Sosaya-Mercier team would take their interests a little further by creating GEC (Grupo de Experimentacion y Creacion) being joined by guitarist Oscar Zamora, this allowing them to position themselves as an electro acoustic creative alternative. That same year, under Sosaya’s auspices the conservatory acquires a SY 77 Yamaha synthesizer. The group produces a concert, which takes place at the Goethe Institut, where electro acoustic pieces by Gilles Mercier, Rafael Junchaya, Jose Sosaya and Cesar Bolaños, besides instrumental pieces by other Peruvian composers, were presented. As a result of these experimentations by GEC, Gilles Mercier produced in 1994 one of the most special pieces of this period, Improva, for processed guitar, synthesizer and computer, and premieres it that same year. The author labeled his piece as Kagel influenced in reference to the avant-garde composer Mauricio Kagel.

That same year Sosaya travels to Madrid with a scholarship for a brief residence at the Laboratorio de Informatica y Electronica Musical de Madrid (LIEM) which resulted in the composition of his electronic piece, Evocaciones.

The sum of these experiences had already created the seedling for Jose Sosaya to found the Taller de Musica Electroacustica del Conservatorio Nacional in 1995. Thus a small laboratory with very basic elements, a SY77 Yamaha synthesizer, a small 8 track mixer and a Pentium computer with a Cubase software, was created. That tiny equipment constituted itself as our brand new first official electro acoustic music laboratory in Peru. And approximately twenty compositions were created there in a time span of two years divided in four terms. The following students from the careers of composition and musicology enrolled: Nilo Velarde, Julio Benavides, Renato Neyra, Federico Tarazona, Fernando Panizo, Eduardo Suarez, Alipio Bazán, Carlos Mansilla, Cesar Morillo Benavides, Andy Icochea y Daniel Sierra. (6)

Of all of these composers only Julio Benavidez, Nilo Velarde and Federico Tarazona would develop a greater interest for electro acoustic composition. Benavides would later be in charge of the course on electro acoustic composition at the National Conservatory. Tarazona would continue his studies on electro acoustic composition in France apart from having a relevant career as a charango player. Amongst his pieces one can recall Metarongosofia Nº 1 (1995) and Nº 2 (2005), in which he uses sound samples from the charango which he processes electronically, creating a sound weaving with great texture richness.

At the same time this small laboratory appeared other Peruvian composers living abroad were producing important work. Such is the case of the already mentioned Edgardo Plasencia, a most prolific composer with an ample specter of work. His series of compositions Fractal Songs (1993) is remarkable as is the series of pieces composed between 2001 and 2003. Another special case is that of Rajmil Fischman, based in Keele, England, who in some pieces shows the use of sonorities from the Afro Peruvian tradition. Formed at the University of York, England, he has composed a large number of electro acoustic pieces as well as audiovisual works and above all mixed pieces, amongst which one has to mention Los Dados Eternos (1994), for oboe, tape and live electronics, which is probably one of the most ambitious Peruvian electro acoustic pieces of this period. The electronic piece Sin Los Cuatro (1994) was composed with a Composer’s Desktop Project (CDP) program using an Atari ST. In 2007 the Canadian label EMF released a record with his electronic compositions called A Wonderful World.

Besides Rajmil, another important Peruvian composer who has taken his career abroad is Cesar Villavicencio, based in Sao Paulo, Brazil. With some collaborators he has made an e-recorder, an instrument which can record and process sounds live. He has also developed a whole theory concerning improvisation and the use of electronic instruments. The mixed piece Mundos (2000) for processed traditional instruments is one of his most important pieces.

The era of access

By mid 90s Peru had been able to control its severe economic crises. The arrival of internet promoted great access to information which translated into a diversity of musical styles becoming known. Add to this the socialization of technology as a consequence of prices for PCs and laptops dropping significantly. As Julio Benavides well put it in a recent interview: “I stepped upon technology as it was the cheapest instrument to generate sonic objects”. For the new generation of Peruvian electro acoustic composers the scope is different. By 1995 Alta Tecnologia Andina, which would be in charge of organizing the Electronica video art festival, begins to operate and it is then that all of a sudden a different category becomes legit locally: it is that of new media, a flexible category governed essentially by the media used, meaning electronic media, new technologies. The Festivales de Video Arte in Lima are a sign of the art boom with new media that will also allow for electro acoustic music to come out, even though shyly, from its strictly academic space and composers come together with electronic artists and video artists. The renewed world of visual arts in Lima by the end of the 90s opens space for experimentation with new media and suddenly in the same space you find electro acoustic music, experimental music, improvisation, noise, etc. And many young artists occupy that limbo where different traditions come together in accordance to that hybrid attitude of diluting frontiers which characterizes contemporary musical proposals. That is the case of the new electronic composers who become known in the 2000s, such as Jaime Oliver or Renzo Finilich who shall write a new chapter for electro acoustic music in Peru.

This compilation brings together for the first time the Peruvian electro acoustic music produced in the 90s which implies the arrival of a new generation of Peruvian composers interested in creating with electronic media, showing a diversity of aesthetic options. This marks the beginning of the use of computers and software for local electro acoustic productions and it becomes an essential document to know and important link in the recent history of electronic music in our country.

edition of 300 copies