In 1973, avant-garde ensemble Creative Associates goes on a tour of Europe with Eastman’s brand new piece in their repertoire, and in short: “Stay on It” turns the coordinates of avant-garde music on its head. It is minimal, but unashamedly groovy; it is open to improvisation, grants performers all the freedom they could need, but it isn’t jazz and never slips into the non-committal. It is open to theatrical and performative elements, but also to the poetic and lyrical. It is strict and demands maximum concentration from its performers, but releases them into playfulness. Once the musicians have gotten used to the discipline, have adopted the groove that Eastman demands of them, a vast field of new connections opens up to them, leading to sublime sonic unions.

“Players may choose to play and repeat the layered cells at their own discretion,” the playing directions for the piece read. And: “Each element (Theme, Cells) may be repeated ad lib. Cues to move to each next section may be visual, or a pre-determined musical cue.” It is clear that Eastman is writing for a collective of intelligent, cooperative, well-informed musicians. “Stay on It” is about respect, mutual support in seeking and finding, about an openness to the world, in which people strive for self-liberation and in which the boundaries between classical and pop music collapse, because they represent false hierarchies.

1973 – Eastman has a stipend at the University at Buffalo’s Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, he is taught by Morton Feldman, fostered by legendary conductor Lukas Foss, is already known as a singer and performer, and Petr Kotik and the Creative Associates finally want to put his pieces on the concert stage. And everyone knows: Julius Eastman is serious about there being a close link between political change and musical emancipation.

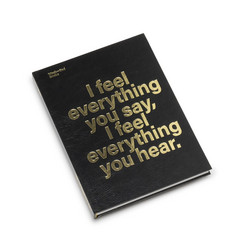

Cut to 1981. Eastman releases “The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc”. Where has the lightness gone? The relation to pop music? The love for the musicians who have to develop the piece during its performance? “The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc” sounds like heavy metal: forceful, dark, urgent, sawing – and then lamenting, heartbreaking. Eastman writes a programme text for the premiere, in which he pronounces the piece “a reminder to those who think that they can destroy liberators by acts of treachery, malice, and murder. They forget that the mind has memory. They forget that Good Character is the foundation of all acts. They think that no one sees the corruption of their deeds, and like all organizations (especially governments and religious organizations), they oppress in order to perpetuate themselves. Their methods of oppression are legion, but when they find that their more subtle methods are failing, they resort to murder. Even now in my own country, my own people, my own time, gross oppression and murder still continue.”

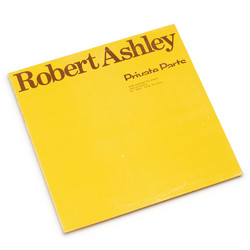

“The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc” is one of his last known pieces. Even back then he seemed to be in danger of shattering into pieces against the repression of this period, against himself, broken by the grinding down of any hope of liberation. The two pieces – from 73 and 81 – mark the poles of Eastman’s music. Awakening and dark foreboding: an aesthetic that could barely be any more provocative and challenging stretches out between them. They were released for the first time in 2005 on CD (the compilation “Unjust Malaise”, New World Records). Now they will be released on vinyl. Julius Eastman is still to be discovered. And we discover him anew with every listen.