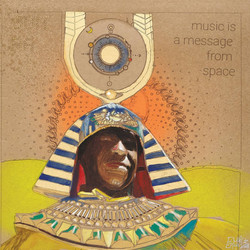

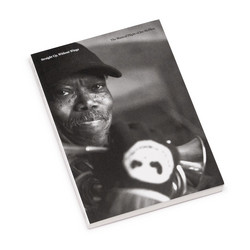

The African OmniDevelopment Space Complex/We New is the brief—66 pages long—but engaging memoir of Ronald Ubadah McConner, aka Ra’maat Ubadah Hotep Ankh McConner Iheru (1939-2020), a bassist, creative music advocate, and community catalyst who ran a music and cultural center out of his home in Pontiac, Michigan for several decades.

In the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s Pontiac, and the Detroit area more generally, was a hotbed of jazz, being home to many fine players such as the Jones brothers—one of whose nieces McConner married. McConner writes about being exposed to the music as a child through the records his mother played at home, and by his teens he and his twin brother Rashid began building extensive jazz libraries of their own. For McConner, jazz was something that was always there, through high school, through four years in the Air Force, and through thirty years working for General Motors, experiences he recalls with a genuine affection. Moving back to Pontiac after his four years working at the Hunter Air Force Base Hospital in Savannah, McConner continued to nurture his love of the music by attending performances at area clubs—The Minor Key, the Drome Showbar Lounge, The Spot Bar, LaRoach’s Tea, Baker’s Keyboard Lounge—to hear visiting artists as well as players from the vibrant local community. Eventually, he became an active participant as well as an enthusiastic listener.

McConner was attracted to the double bass early on, and finally acquired one in autumn, 1969. With his brother Rashid on trombone and Ahmad Jihad Malik Shabazz on drums, he formed a trio called The Fireworks Art Ensemble; they played an appropriately incendiary music McConner describes as being “based on sound, strength, feeling, and lengths of time.” The trio got together at Ahmed’s African Import Shop and played small clubs, restaurants, colleges, community centers, and even street corners, basements, and playgrounds. McConner got together with many other local musicians as well to play improvised music that “would really go ‘OUT’…we just played as hard as we could, as long and as loud as we could and let the spirit take over.” The spiritual dimension of the music rather than any technical concerns was what really mattered for him—to play “exclusively what it is you feel in the moment, something never even conceived, something raw, guttural and utterly spiritual.” McConner fostered this vision of a spiritually-based improvisation by encouraging others to explore it. In the early 1970s, he began hosting Friday night sessions for music, conversation, and fellowship at his home, which he called the African Omnidevelopment Space Complex/We New. Many musicians passed through it over the years; it was an important community institution that endured into the early years of the new millennium.

“Community” is the key here, but in no narrow sense. From the point of view of the larger jazz industry it would be easy enough to characterize McConner and his Friday evenings as “just” a local phenomenon that fell outside of the broader music marketplace. But in his afterword to the book, alto saxophonist patrick brennan, a participant in McConner’s Friday night sessions from 1972-1975, makes the important point that such a characterization would only miss the point. Music, and its role in the life of an individual and a community, is a more complex, and vital, thing that validates itself and is validated by the effect it has on those who encounter it and above all, on those who are affected by it and live it in a deeply meaningful way. McConner certainly did live it, and encouraged others to live it as well, and did it all in a broadly welcoming spirit. In fact what comes across most vividly in this memoir is not only McConner’s obvious passion for music, but his profound generosity of spirit. That the two can be, and even should be, intimately connected is the greater message of the book.