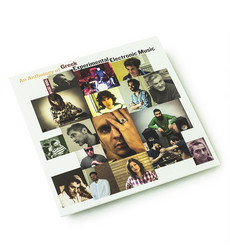

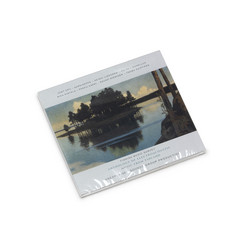

Various

Anthology Of Experimental Music From Japan

Modern-day noise music has escaped the preserve of academics and avant-garde thinkers, uniting conservatory-trained and untutored participants from the worlds of punk, jazz, metal, contemporary classical, electronic music, and sound art in an exuberant and egalitarian collision. While noise conjures up the image of a cacophonous maelstrom of sound, contemporary improvisers utilize a much broader tonal palate, often offsetting abrasive textures with environmental sound, field recordings, and even silence.

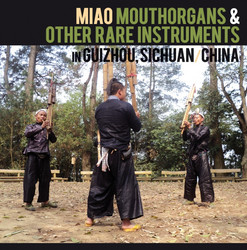

This is especially true in Japan, which has become a global center for the genre. Artists including Haino Keiji, Merzbow, Ōtomo Yoshihide, and Hijōkaidan rank among the scene’s most respected and influential names. So synonymous, in fact, is the country with this style of music that the term “Japanoise” was coined to provide a convenient catch-all. Some of the elements of traditional Japanese music seem to a novice like mere “noise” and have clear parallels in modern experimental music: a relative absence of harmony; the dissonant tonal clusters produced by banks of shō mouth organs in the court music called gagaku; the spluttering, wheezing, trills and flutter-tonguing of the shakuhachi; the stop-start rhythms, droning, repetitive vocals, and shrill, unmelodious flute of nō and kyōgen drama; the strident, uartertone jōruri narration and plink-plonk samisen that accompany bunraku puppet theater; and the gaping silences and austere arpeggios plucked out on traditional string instruments like the koto and biwa.

No wonder a music coming from the merging of such tradition with new music developments from the West had to take its direction to something “other”.