Since launching in 1984, the American label Mode Records has been one of the world’s greatest outlets for new music, devoting itself to chronicling the history of contemporary classical music in the US as well as presenting groundbreaking new work from around the globe. The imprint has famously maintained multi-volume editions that memorialize some of America’s greatest figures, including John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Roger Reynolds, to say nothing of European titans like Gyorgy Ligeti and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Still, one of Mode’s most valuable endeavors has been its ongoing devotion to presenting the wide-ranging work of German composer Walter Zimmermann, one of Europe’s most unique and influential voices.

One of the most generous, open, and influential figures in contemporary classical music, Walter Zimmermann built his fruitful career by trusting his instincts and innate curiosity to amass a brilliant and richly varied body of work. Born in 1949, he studied with Werner Heider and Mauricio Kagel, followed by a stint at the Institute of Sonology in Utrecht, and further time exploring computer music at Colgate University in New York. He’s an important scholar, and during a period when many European voices were satisfied with the activities and ideas bouncing around the continent, he traveled to the United States in the mid-1970s to conduct research on the paradigm-shifting ideas of American composers like John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Alvin Lucier. When he returned to Germany, he established Beginner Studio in a former factory in Cologne—presenting concerts and giving lessons—in a decidedly non-academic setting. He relocated to Berlin in 1986, continuing to teach and write both richly varied music as well as thoughtful essays and books on contemporary music.

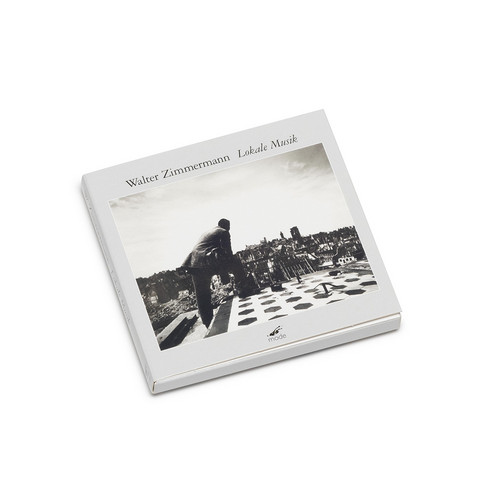

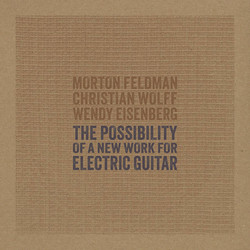

Over the years Mode has operated to give Zimmermann a solid platform, issuing both new work and reissuing lost classics. In 2019 the label reissued the entirety of the composer’s 1982 triple-album masterpiece “Lokale Musik”, including some newly recorded material, followed two years later with “Voces”, a lavishly packaged 3CD box focusing on Zimmermann’s vocal music from 1979-2016. Mode also reprinted the composer’s invaluable book “Desert Plants”, the fruits of US research, which collected fascinating interviews he conducted with the likes of Cage, Feldman, Lucier, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, James Tenney, Joan LaBarbara, Charlemagne Palestine, Pauline Oliveros, Larry Austin, and Christian Wolff, among others.

Mode continues this essential project with the first-ever reissue of Zimmermann’s first recording, the solo piano classic “Beginner’s Mind”, composed around the same time he opened his Cologne studio of the same name. A subsequent account was recorded by British pianist Ian Pace in 2000, but the original has been out of circulation for decades. The piece was deftly performed by German new music specialist Herbert Henck—a definitive interpreter of works by Cage, Ives, Boulez, and Barlow, among others, whose work is well represented on labels like ECM, Wergo, and Edition RZ—and released by the composer’s own Beginner Records in 1978. In his program note the composer calls it “the result of my study of the contemporary European new music scene,” citing the twin influences of Erik Satie and Cage, as well as ideas gleaned from Shunryu Suzuki‘s book “Zen Mind”, “Beginner’s Mind”. In fact, the written outline that accompanies the score reads like a series of Buddhist koans that complement the surface simplicity of his elegant music.

Zimmermann wrote the piece using fragments of previously recorded piano improvisations, and there is a deliciously halting quality to the work, as if the performer is translating a shuffle of shifting thoughts to the instrument in real time. The score asks the performer to use their voice here and there, and we can hear Henck clearing his throat before making his first utterance, wordlessly limning some of the melodies, speaking, and setting up the concluding “Beginner’s Mind Song”. It’s a work of incongruous simplicity and rigor, and we couldn’t be happier that it’s finally back in print.