This Da Vinci Classics album stems from a friendship and a cooperation. Its protagonists are two musicians, Walter Prati and Alvin Curran, each contributing his own experience, musical principles, creativity and openness to artistic encounters. Walter Prati’s musical background is as unusual as it is fascinating. He describes it as a “mix of non-academic provenances and academic experiences”. His first approaches to music performance date back to his early teens, when he began playing the bass in a rock band with his fellow students at secondary school. (Half-jokingly, he reveals that his choice of the bass guitar was not entirely deliberate: a bassist was needed, and, moreover, the bass had fewer strings than the guitar, so… it was probably easier to play!). Later, and almost by chance, he had his Damascus moment when listening to a work by György Ligeti. From that point on, his musical itinerary was at the crossroads of diverse musical worlds: from psychedelic rock to Ligeti, from Jimi Hendrix to the free jazz of the Sixties, which he learnt to appreciate some years later. “There was a melting pot of many musical interests, and I transferred this experience into the extemporaneous playing style I had in those years”.

At the same time, Prati befriended young musicians who were attending the Milan Conservatoire and the contexts of academic music. Little by little, he entered that world himself: he began to play the double-bass, then applied to the Conservatory course of electronic music (in 1978, with Paccagnini), and finally followed courses of composition under the guidance of Irlando Danieli.

While learning the different languages and technique of musical composition, Prati tried his hand at electronic music in combination with the world of “radical improvisation”, with which he always remained in close contact. In the Eighties, Prati found his voice as a composer, building his musical identity both technically and esthetically. The value of his creations was acknowledged by many, and he won several competitions with his compositions of electronic music. Since then, he always tried to stay at the threshold between the two worlds of “composed” (i.e. written) music and improvisation. Whereas these two worlds are considered as antithetic by many, for Prati they equally contribute to his musical profile. This approach corresponded to his deep artistic aspirations, but led to frequent misunderstandings and misapprehensions in the musical establishment. “I always found it difficult to find opportunities for musical encounters here in Italy. In the composers’ eyes I was an improviser, and a composer for the improvisers. I had always to seek and find the borderlands of composition and improvisation. As the years went by, these borderlands became increasingly narrow, and presently they are really limited”.

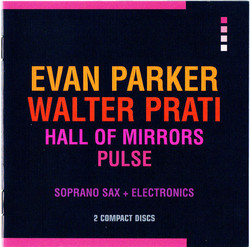

In the Nineties, Prati resumed his collaboration with Evan Parker, with whom he had followed a seminary during his student days, and for whom he had created his first important composition. Prati participated to Parker’s ensemble since its inception, in 1992; together, they realized concerts, tours and recordings for ECM. “It was not just an important recognition for our work, but rather a test for it. To record our music meant that it was worth transmitting to future generations”, as Prati explains.

In the subsequent years, Prati continued cooperating with many musicians, always trying to create “clashes or layers”, as he puts it, between composed and improvised music.

This interaction was fostered and facilitated by the use of electronic music: “It broadens the horizon because it permits many operations”, as Prati affirms. For example, non-electronic instruments may be played in an improvisation, while electronic instruments may be used in a more precise and defined fashion, or vice-versa. This experience may encompass that of an absolute freedom, as happens when no previous agreement is established among the musicians. “In those cases”, as Prati puts it, “all happens at the moment when the other is perceived with his music”. These experiences proved to be very fecund also from the pedagogical viewpoint. Prati teaches Electroacoustic Musical Composition at the Conservatory of Como, and gives seminars about the techniques of musical improvisation. The encounter of written and improvised music is a formidable resource in the educational field. “This kind of improvisation is not grounded on aesthetical rules, as for example in the case of jazz improvisation. In that or in similar cases, improvisation happens within the framework of established aesthetical principles, and one needs to master a specific musical attitude. Here, what matters is to be familiar with the musical attitudes of the various musical worlds; to be able, in other words, to identify the intervals or musical gestures which are typical for a particular style. Although this can be just a superficial image of a specific repertoire, it leads the listener to a particular musical world”. Eclecticism, or the capability of freeing oneself from the constraints of labels and classifications, is what characterizes also the aesthetics of Alvin Curran, the other musician represented in this recorded. As he writes of himself, his experience of music encompasses many seemingly contradictory realities. Similar to Prati, he appreciates the possibility of crossing the boundary between composition and improvisation, and enjoys the attempt to reconcile tonality with atonality. His large compositional output includes works for classical instruments (such as the piano or the violin), others for instruments at the crossroads between “cultivated” and folk/ethnic music (such as the accordion or the shofar), and others with taped and sampled natural sounds, synthesizers and computers. Among his foundational experiences was one in a “radical music collective” based in Rome, in the mid-Sixties. “Musica elettronica viva” – this was the ensemble’s name – was an attempt to explore the various dimensions of sound and of the human and artistic relationships it enabled and favoured. His various fields of activity include numerous audio/visual installations, in cooperation with visual artists, as well as a core interest in pedagogy and education.

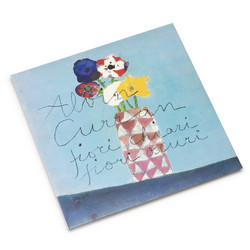

In Prati’s words, Curran’s role in today’s musical scene is fundamental: “He has been and still is not only a witness, but rather a protagonist and an actor throughout several decades of important musical experiences. He has powerful ideas; ideas resulting from his long reflections. He is the torch-bearer of an attitude to improvisation with which I’m fully in agreement”. The two musicians’ friendship began many years ago. “We always said that we had to make something together, but it never materialized”. In 2019, however, Curran had planned to stay in Milan for a while, and the opportunity came for scheduling a joint recording session. The principle behind it was to create an improvisation “led” by the instruments. The two musicians established which instruments were to be used: the sound medium thus became the stimulus for artistic creation. “The instruments paved the way for us”, says Prati, “through their sounds, technique and performance practice”. Such an improvisation can only take place when the musicians practise an extreme form of concentrated listening. “When musicians encounter each other, they listen and consequently change their performance style. Whenever I met and performed with other musicians, the final result was always something different from what I could have done in my routine creations”. After the recording sessions, the musicians had produced five recorded tracks; four of them are included in this album, and each represents “a different world”, in Prati’s words. For example, the third track is entirely made of electronic sounds, and this feature is atypical for both musicians. Their encounter, therefore, resembles the “community garden” evoked in the title of this album. The idea for the title is Curran’s, and, for Prati, “it mirrors the reality of our encounter and of what is heard”. The CD cover displays a picture taken by Prati himself, and portraying a composition of seeds and weeds, such as are typical for community gardens. “It is the confluence of various aromas, flavours, spices and kinds of music. As happens with all musical works whose style goes beyond the usual ones, openness is required of the listener, whose perception is stimulated. It is important to be attentive to every detail, and to welcome unusual experiences. Music is for all, but not all are for music… It is the individual’s choice”.

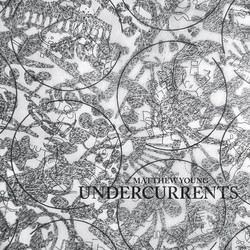

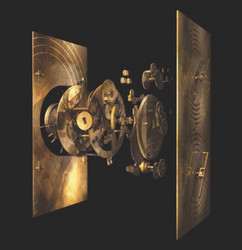

The organic image of the garden and of the vegetables is also a reminder that electronic music possesses an ecology of its own. This music germinates from the human relationship between two artists, and it employs the digital media “as instruments”, not as ends in themselves. They are in the service of the artists’ inspiration and of their musical dialogue; they are similar to the gardener’s tools, whose end is to serve the growth and flourishing of a luxuriant garden. St Ann’s, is a tribute to the council estate, on the edge of Nottingham city centre that defined Boulter’s formative years: “I was born in the old St Ann’s. Famously documented in the late 60s as some of the poorest social housing in England. Crumbling, cramped, and full of damp. We had a shared toilet in the backyard and no bathroom, some of the houses were without hot water, it was freezing cold in winter. Everything seemed black and white.” By the late 1960s, St. Ann's, like many other city centre areas, had become run down and was earmarked by the council for slum clearance. 340 acres were bulldozed and 30,000 people including David's family were compulsorily uprooted. In 1970 the Victorian streets were replaced with a Radburn-style estate.

“We moved to the new St Ann’s when I was six. There were two indoor toilets! A bathroom with a shiny white ceramic bath that you could fill whenever you wanted. Central heating, and a small garden at the front and back of the house. We had our own shed, and a cherry blossom tree just over the fence. Everything came into colour.” Subtle use of guitar, double bass, vibraphone, tenor recorder and field recordings conjure up the old streets of cobble and slate, damp brickwork and grey skies, juxtaposing the newer post-1960s world of pebble dash and green grass, fresh air and a brighter future. “After we moved to the new house, I still went to the old Victorian school, until it was demolished about a year later. It was very strange to walk to school through all the old houses and streets while they were being torn apart.” This is a record full of personal memories, but it also tells the tale of Britain’s inner cities and their renewal in the 60s and 70s.

“At the end of 2022, my Mum could no longer live alone in our house. I spent Christmas packing belongings and emptying it, what to keep, what not to keep? The emotions and memories were intense. There was still the same carpet on the stairs that my Dad had put down when we’d moved in. I’d already started to make some music that I knew had something to do with Nottingham, and the streets I’d spent my childhood wandering. When I arrived back home in Prague, the feelings poured into the music. I grew up in St Ann’s and lived around the area until I left for London when I was 25. This LP is a celebration of a community, streets that still hold a special place in my heart. I will always be from St Ann’s and St Ann’s will always be a part of me.“