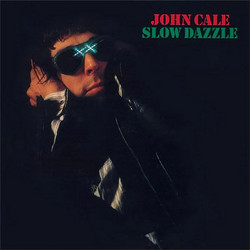

John Cale was never very kind to his solo debut, Vintage Violence. When it was released in early 1970, Cale had been out of The Velvet Underground for less than two years. He wanted to prove he could be the songwriter, the person penning the words and melodies behind which a band could work. “I was masked on Vintage Violence,” he wrote much later. “You’re not really seeing the personality.” Indeed, Cale’s personality as a polyglot seemingly interested in everything emerged more and more on his next two solo albums, his only two for Reprise: 1972’s bracing and exploratory classical sojourn, The Academy in Peril, and 1973’s masterclass in anxious but accessible songcraft, Paris 1919. By reissuing both records in tandem, it reaffirms the artistic fearlessness Cale then fostered at the edge of 30, when all of music seemed like one inviting playpen.

“Revisiting work from the past is a double-edged sword for me. Of course, it’s bound to happen when you've been making music for 60 years or so. . . What's unique about this process with Domino, is their desire to get it right. Not merely re-issue something for the sake of an anniversary or racking up a catalogue favorite - but finding new treasures and highlighting what made it special in the first place. After hearing the test pressings, it occurred to me that the new mastering was a major part of how these works will be presented, rather than simply being preserved. There are moments of clarity and even a laugh or two had by revisiting not only the music, but recalling the sessions (and antics) that made up what became these two recordings. It is my pleasure to share these with you . . . again.” – John Cale, September 2024

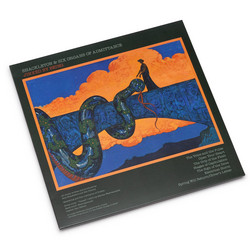

Taking a sidestep from his earliest solo efforts into an exploration of his classical training and influences -- thus the title -- John Cale on Academy creates a set of songs that probably bemused more than one listener at the time of release. The predominantly instrumental release, which finds him working with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on two tracks, steers away from the more grotesque classical/rock fusions at the time to find an unexpectedly happy and often compelling balance between the two sides. Opening track "The Philosopher" signals this well, with a low-key acoustic guitar/drums rhythm accompanied by separate horn, string, and keyboard lines. The sound is at once thick and remarkably spare, a rejection of flash for mood setting without aiming toward the drones so prevalent in much of Cale's initial work.

Restrained humor crops up throughout, a smart way to undercut any fusty claims of pretension. "Legs Larry at Television Centre" has Cale acting like a very uptight, controlling TV technical director "directing" the string quartet performance at the center of the song. "King Harry," the only song with lyrics, is a memorably whispered zinger at the dying figure of King Henry VIII, with Spanish and calypso touches on top of everything else. Much of the time the mood is, quite simply, serene and beautiful, an exercise of Cale's skills that impresses both technically and emotionally. "Brahms" is a fine example, a piano solo piece (thanks are given by Cale in the liner notes to Ron Wood, though what connection the then-Faces guitarist has to is unclear). When things are more quick in mood, as in "Faust," one of "3 Orchestral Pieces," one of the Philharmonic guest numbers, Cale has good fun applying rock arrangement and production tricks: compression, gentle flanging, drum rhythms, and so forth. - Ned Raggett, Allmusic

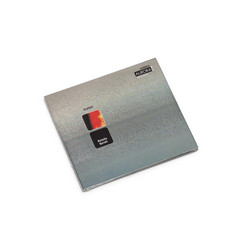

- Artist-sanctioned reissue

- Remastered from the original tapes by Heba Kadry

- Replica promotional insert & sticker

- Download includes bonus track - Temper

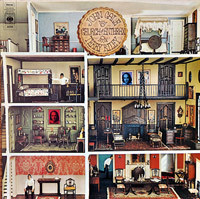

Reissued on 180 gram vinyl in a replica die-cut flip gatefold cover.

Tracks A2, B1 and B4 recorded at Shipton Manor, Oxon, England.

Tracks B3 and B5 recorded with The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at St. Giles Church, Cripplegate, London.

Mixed at Air Recording Studios, London.