Rodrigo Amado, Chris Corsano

No Place to Fall (Tape)

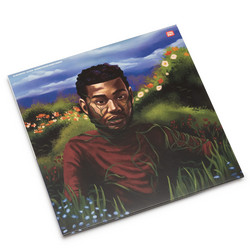

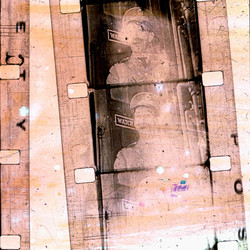

**First pressing of 175 copies with red cassette shells** The longer one works as an artist, the more secure one’s own identity becomes — whether visual, sonic, textual, or otherwise, the goal is to be clearly oneself. It may seem overly simple to cut the fat and center on creation and individuality, but considering those who have gone before and died for their art, the gambit seems far from easy. Saxophonist and photographer Rodrigo Amado (b. 1964, Lisbon) has worked in two different but related streams for nearly forty years, performing improvised music and capturing abstraction in daily life. Both paths are challenging on their own, but to engage them with equal energy requires a significant amount of dedication and little time to waste.

Amado has been active in a variety of free music contexts from the late 1980s onward, including chamber-like groups such as the Lisbon Improvisation Players and trumpeter Sei Miguel’s ensembles. As with a number of full-tilt tenor saxophonists, Amado’s most fruitful linkages have been with drummers – Stefan Gonzalez, Paal Nilssen-Love, Gabriel Ferrandini, Luis Desirat, Lou Grassi, Marco Franco, and Gerald Cleaver. A bullish early trio featured Nilssen-Love and bassist Kent Kessler and released two discs on the saxophonist’s own European Echoes imprint. In 2012, he and Kessler formed a quartet with veteran saxophonist/trumpeter Joe McPhee and drummer Chris Corsano. That group has released two discs thus far, This Is Our Language and A History of Nothing (on NotTwo and Trost, respectively). A collaborative axis rooted in existing partnerships, it was natural that Amado and Corsano might initiate their own dialogue and spin off into new areas, which they’ve done on the five improvisations on offer here.

Amado notes that he got “completely into” the drummer’s playing after hearing his duos with saxophonist Paul Flaherty, including cornerstone albums like The Hated Music (Ecstatic Yod) and The Beloved Music (Family Vineyard) as well as free-rock collaborations with Sunburned Hand of the Man and guitarist Ben Chasny. As he put it in an email, “I knew Chris was one of the musicians I wanted to play with if the opportunity would come.” Speaking about the 2012 formation, the saxophonist says that “for the drums, I wanted someone to make a contrast with Kent, more abstract. That's the way I think about Chris – he’s an ultra expressive and sensitive player with a deep level of abstraction, but never loses sight of the form. He’s also a dynamo, the way he makes the music ‘explode’ at certain points, conducting the dynamics of the band. When I think about Paal Nilssen-Love’s playing, for instance, I think he is a more organic player, more intuitive, linked to the roots. Not that Chris can’t be those things, he certainly can, but he then balances all this with what seems almost like contemporary classical elements and a deep abstract approach. With him I feel really free to create and invent. I know Chris can keep up with any direction I take in a totally coherent way. So, that’s what he brings out in my playing, confidence and freedom.”

But this recording is a more focused lens on structured free interplay; neither improviser is a stranger to the format, and both have found much fruit in duo exchanges. As Corsano puts it, “going from the quartet to the duo was interesting to me because I could focus totally on Rodrigo’s playing… the way that he develops a specific arc or feeling. What strikes me most, I’d say, is that he gets down to business. There is a strong driving force there, which is fantastic for a drummer to respond to and join in. I remember the duo recording session feeling very natural and unforced, probably thanks to that interaction.” Corsano is an incredibly limber player able to transcend stylistic areas from open-form jazz improvisation to scuzzy blues rock and surging drone. Coupled with Amado’s incisive and ferocious guttural scrawl, they make a formidable pair, the drummer’s allover footwork and taut web an active, supportive environment for throaty nods to the masters (including a touch of “Giant Steps” on the title piece) and blistered abstraction.

Central here is is the sheer joy of back-and-forth play, whether conversational or nudged in a sparring direction, as evidenced on “Don’t Take It Too Bad,” which advances resonant jowly puffs and dry, shimmying waves with supple midrange poetics. The closing “We’ll Be Here in the Morning” is the closest thing to a ballad in the set, a materialist caress of keys, ligatures, breath and brushes, a dewy landscape of subtle drive and husky purrs that, in time, evinces wry steel. The pair demarcate the sound of wide-open spaces (McPhee’s vast tenor echoes distantly through the proceedings) but gently moving into coiled, energetic dialogue, Amado and Corsano remind us of their music’s presentness.

The formal play of representation and history is interesting, and while too much can be made of a visual artist’s traffic in sound or vice versa (Amado is quick to note the danger of spuriousness), the tension between identifiable forms or narratives and the purity of color, shape, or line is something shared among media. Amado’s photography captures recognizable individuals, spaces, and situations with a raw, sometimes arid distance and playful surreality. Here, he and Corsano trace lickety-split freebop convention and balladic airs with the elemental gravity of a paint scraper or blowtorch, taking the recognizable and turning it inside-out. As creative, instantaneous inventors, structure, melody, and swing are apparent throughout No Place To Fall, but each factor is made malleable, sheathed in raw, transcendent feeling and the squall of here and now.

“At a certain point, there is only good and ‘gooder’” — Bill Dixon

![The Key (Became the Important Thing [& Then Just Faded Away])](https://cdn.soundohm.com/data/products/2024-07/Corsano_TheKey_LP_01-jpg.jpg.250.jpg)