Jackie McLean

One Step Beyond To New And Old Gospel (Revisited)

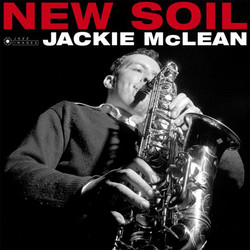

Temporary Super Offer! "One Step Beyond is rightly seen as a pivot point in Jackie McLean’s evolution, but its adventurousness was not without precedent. As A.B. Spellman noted in Four Lives in the Bebop Business, “Quadrangle” – the opening track for 1959’s Jackie’s Bag; it was first recorded as “Inding” for Lights Out!, a 1956 Prestige date – “involved an elaborate group construction that [McLean] was afraid was too far-out,” so he used “I Got Rhythm” changes to mainstream it, which he later regretted. His decision may have been related to the revocation of his cabaret card, making him more reliant on commercially successful albums to make ends meet. By late 1961, McLean was more confident in stretching his music beyond the parameters of hard bop he helped codify, fortified by a two-month stand at Chat Qui Peche in Paris, where he befriended painter Bob Thompson. This is reflected in the second Blue Note album he recorded upon his return, Let Freedom Ring, recorded in March 1962. Spellman opined that the album was “a decided break with his past.” Although it features an early foray into modal composition and startling upper-register screams in his solos, it is not an altogether clean break, as McLean also included an original 12-bar blues and “I’ll Keep Loving You,” penned by his early mentor, Bud Powell.

By the end of 1962, McLean was feeling the undertow of the new wave in jazz and the need to form his first working band since 1958. The first two pieces of the puzzle McLean put together were Grachan Moncur III, who had woodshedded with him earlier that year, and Tony Williams, the 17-year-old phenom who was part of a Boston rhythm section McLean gigged with in December (with his mother’s permission, the drummer moved in with McLean’s family at Christmas, so that he could dive into the New York scene). With less than a week before a stand at the Coronet in Brooklyn, McLean brought on Bobby Hutcherson and Eddie Khan, rounding out the quintet heard on One Step Beyond. The inevitability of McLean distilling aspects of the new jazz is reflected in the opening pronouncement of his liner notes: “One step beyond is the direction by which creative man has been moving since time began.” Perhaps unintentionally, his use of upper-case letters and italics emphasized his taking a single step, not a quantum leap. The idea that McLean was an incrementalist is supported by both his compositions and his solos. “Blue Rondo” is proto- typical freebop, a repeated, tightly coiled figure that gives way to blues changes. While McLean’s solo is teeming with his signature searing bluesiness, he occasionally colors outside the lines with against-the-grain phrasing and strong textures.

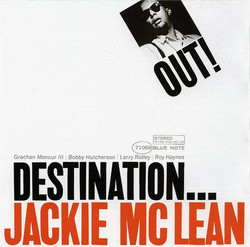

“Saturday and Sunday” is a more decisive stride forward, as McLean uses contrasting melodies to represent joyful release and sober reflection. The unusual construction of minor-key chord changes also gives McLean the opportunity to push the envelope harder in his solo. The evolution of established artists is often marked by their endorsement of, and collaboration with, promising newcomers. That is the case with McLean and his quintet, all of whom McLean enlisted when they were free from ironclad obligations: Moncur had just left Ray Charles; Hutcherson had weeks off from his steady gig with Al Grey and Billy Mitchell; Khan worked around his schedule with Max Roach; and Williams was literally in-house. In the case of Moncur, McLean devoted half of the album to the trombonist’s compositions, which McLean discussed before his own in his liner notes. Both “Frankenstein” – a pithy name for a jazz waltz – and the evocative “Ghost Town” are further evidence of McLean’s determination to move ahead. Weeks after recording the quintet’s second outing for Blue Note – Destination ...Out! – McLean performed on Moncur’s debut as a leader, Evolution, along with Hutcherson and Williams.

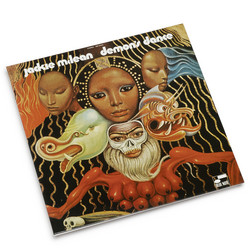

The threads of inevitability, endorsement, and incrementalism, would again entwine in 1967 with New And Old Gospel. Nat Hentoff’s liner notes begin by quoting McLean about the inevitability of recording with Ornette Coleman, who, almost a decade after his first recordings, was still a polarizing force. Coleman’s detractors were then refueled by the perceived naivety of his violin and trumpet playing, first documented in 1965, making the decision for him to play trumpet exclusively an even more ringing endorsement. However, the shock value of the teaming of McLean and Coleman obscured the significant next step McLean took as a composer. The side-long “Lifeline” is arguably the most ambitious composition McLean wrote in his long, illustrious career. He partakes of some of the expansions of form and vocabulary then percolating in jazz – those represented by Coleman’s thick textures and asymmetrical phrases being the most salient – without compromising the leathered joy and pas- sion of his compositional voice. The four sections span the tornadic energy of “Offering” and the res- ignation of “The Inevitable End,” which boldly concludes with the two horns alone, petering into silence. In between, the plaintive lyricism of “Mid- way” and the driving swing of “Vernzone” suggests that McLean’s is not a straight line, but one with several changes of direction. The contrasts of McLean’s materials and their respective proximities to emergent jazz practices required a flexible rhythms section, one authentic in expressing both hard bop-steeped fundamentals and contemporary extensions. Lamont Johnson’s stretching of McCoy Tyner’s innovations predate Bobby Few’s on Booker Ervin’s The In Between by almost a year. Scotty Holt’s prior work with Noah Howard gave him the insights to navigate the inside and outside passages of McLean’s composition. Billy Higgins was simply the obvious choice for making the twain between McLean and Coleman meet.

Their contributions to the jubilant “Old Gospel” and the probative “Strange As It Seems” give Coleman’s music a fresh accessibility while upholding its tenets. The evolution of Jackie McLean’s music documented on One Step Beyond and New And Old Gospel continued through the solo concerts he gave in the runup to the millennium. He was, to use Anthony Braxton’s term, a restructuralist, who first reengineered the bebop vocabulary, and then gleaned aspects of subsequent movements, always putting his indelible stamp on the resulting music. Each step along the way, he resolutely remained Jackie Mac." - Bill Shoemaker