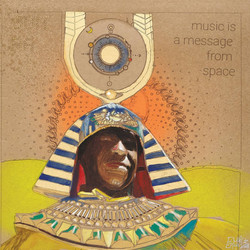

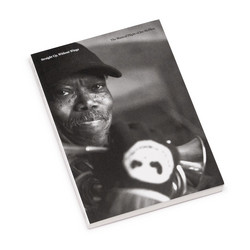

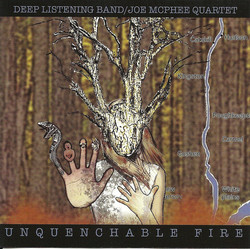

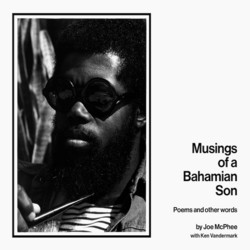

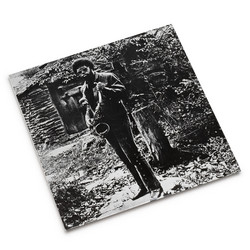

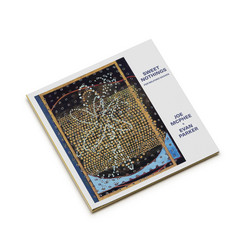

The existence of a free-improvising organ trio, though uncommon even in 2010, shouldn't be all that surprising and, indeed, you might be prompted to ask what took so long. Certainly, figures like Larry Young and Big John Patton stretched the boundaries of organ-jazz in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and composer / pianist / polymath Sun Ra employed the Hammond organ in some of his ensembles (though perhaps those were among his most 'inside' recordings). But for the past few decades, most organ combos have decidedly operated within the tradition set by Jimmy Smith, Richard "Groove" Holmes, Freddie Roach, Baby Face Willette and their (admittedly varied) kin. Which is to say, R&B and soul-grease that, although a beautiful thing in and of itself, has a somewhat fixed aesthetic. Enter Decoy, a British trio consisting of organist Alexander Hawkins (more regularly known as a pianist), bassist John Edwards and drummer Steve Noble. This live set recorded at London's Café Oto is the third volume of Decoy recordings to be issued on the Bo'Weavil imprint, and finds the trio joined by American saxophonist Joe McPhee across three group improvisations, two of which run over the half-hour mark. McPhee is best known as one of the rare improvisers to trace the line between fire breathing and cerebral delicacy, which has made his work valuable in a wide variety of contexts on both sides of the pond. In that light, it's easy to forget that some of McPhee's earliest recordings found him joined by electric pianist Mike Kull and organist Herbie Lehman, on the decidedly funky LP Nation Time (CJR, 1970) and slightly freer but quite relevant recordings for Hat Hut, Black Magic Man (1970) and Survival Unit II with Clifford Thornton (1971). McPhee's tenor playing ranges from fierce blues shouting in up-tempo sections to cottony lyrical flourishes in ballad spaces that recall Ike Quebec. The first, 39-minute, improvisation, "Opening Might," naturally moves through an extraordinary range of colors and instrumental / textural combinations and serves to cement not only McPhee's soulful versatility but also that Decoy does not exist to "deconstruct" a form, but rather breathe an unexpected kind of energy into this instrumental setting. The piece begins as a trio, pointillistic organ jabs approximating electronic music or a Moog (shades of Ra or a particularly excited and plugged-in Paul Bley) supported by Noble's thick, tom-heavy wash and Edwards' throaty arco. Indeed, the contrabass isn't an instrument normally associated with an organ group (the organist's left foot typically plays the bass pedal), but here the bassist's rhythmic and counter-melodic support allow Hawkins a considerable degree of freedom. McPhee enters on soprano with bent, piercing cascades that ride continual crests of fuzz and supple metronomes. It's no secret that Hawkins is an appreciative Ra listener, and like Ra he takes hackneyed saccharine tones and combines them into an inter- associative wonderland before threading events into a canvas of agitated angles and sanctified emphasiz. Clanging gongs, matte skins and bull fiddle conspire in a brief duet before McPhee comments with gooey trills. The saxophonist's second soprano solo finds him approximating something North African in its pinched tonality, wailing and chanting over a slink that threatens to melt before Hawkins explodes into a terse, inflamed minimalism equal parts Young, Mal Waldron and Horace Tapscott. A short breakdown later, McPhee reenters on tenor, at first in small clipped phrases until he begins to tease out a burnished 1940s ballad signification, and Decoy is right alongside him. Hawkins and Edwards temper their rattle into a Freddie Roach / Milt Hinton bag, shaded in with brushy patter in a gorgeous blues walk, though it doesn't take long for McPhee's tenor to erupt in post-Albert Ayler screams as Decoy returns to creating a wallop. As the piece closes out, following a ricocheting exploration in purely improvisational space, McPhee returns with a sinewy tenor line that, once stating its presence is summarily chopped apart, only to be reformed as a pensive John Coltrane-like ballad to close out the improvisation.

Wrenched soprano particulates, dialogued with low organ burbles, begin "Breakout," a somewhat less kaleidoscopic piece that keeps closer to the hedgerow of contemporary free improvisation. Noble's ringing copper and Edwards' horsehairs and gut signal an improvisational yen for brutish physicality, but Hawkins' ornery burble is the main element that keeps Decoy from entirely following free music-tropes. He climbs upward, feeding sputtering aggregations and wet, syrupy runs to a barrage of snare rattle and meaty pizzicato, a merger of clanging time and transcendent grit. As McPhee digs his heels, Noble and Edwards create a tightly woven gallop, the latter's relentless callus- busting pluck impressive as it's buoyed by jaunty B3 comping. The trio has a way of seamlessly working density into quiet meditation, as in the closing minutes of "Breakout" Hawkins' organ is somewhere between Ra's wistfulness and the cool obtuse sound of Gerd Zacher, glinting off short percussive volleys and a pathos-laden tenor declamation. While at first you might be startled by the amount of music being played here (and there are a lot of statements and forms to take in, from all-stops-out freedom to a revelatory calypso), Hawkins, Edwards, Noble and McPhee have created a performance—and a record—for the ages. It will take a number of listens for the music on Oto to sink in, but once it does, it won't be forgotten.