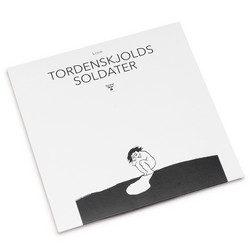

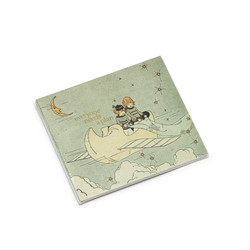

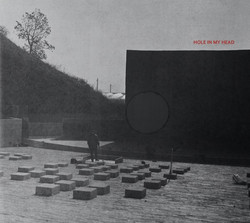

MIMEO - John TILBURY

The hands of Caravaggio

A staggering achievement, one is tempted to call The Hands of Caravaggio the first great piano concerto of the 21st century. The work is the brainchild of Keith Rowe, eminence grise of MIMEO and co-founder of AMM who, inspired by the recently discovered painting The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio, imagined a piece combining the mighty forces of MIMEO's electronics with the pure, gorgeous sound of John Tilbury's piano. Technically, therefore, the work is not really freely improvised, as the musicians were asked to consider the painting (particularly the array of hands within it) and to employ various strategies during its performance. When arriving at the venue of this live recording and surveying MIMEO's set-up, Tilbury remarked, "In one second you guys can eliminate me once and for all." Electronics manipulator Jerome Noetinger deadpanned, "Less than a second."

And this is part of the dynamic at work: the pitched battle and occasional accommodations between the 'orchestra' and the piano. It begins with a low hum to which, after a few minutes, Tilbury introduces the spare yet crystalline chords heíd perfected with AMM, very much out of Morton Feldman in one sense, but also very much his own. As MIMEO gathers strength, it changes form from a comfortable "nest" for the piano to an enveloping storm, flooding the sound-space with a nearly infinite range of sonorities, as chaotic and disciplined as a hurricane. The playing field would have been difficult enough as is, but Rowe threw yet another wrench into the proceedings by having pianist Cor Fuhler play inside the same piano as Tilbury with the motive of not allowing the latter to get into anything resembling a comfort zone. Fuhler tries to anticipate Tilbury's every move and acts to hinder it by damping the piano strings involved, clamping them down, etc. This forces Tilbury into areas that would otherwise have remained unvisited and adds yet another layer of conceptual complexity onto an already deeply rich endeavor. In this context, his playing takes on an almost Romantic quality, not just in the relatively melodic aspect of his approach but also in the heroic striving to achieve a balance against impossible odds. The multi-dimensional, thick conception and execution of the work allows for many repeated listenings that guarantee fresh discoveries each time, both in the actual sounds heard and, perhaps more importantly, in the relationships between musicians and, analogously, between past and present as represented by the two main factions here. The question has been asked: Where does improvised music go after AMM? This is one amazing answer. All Music Guide, Brian Olewnick

And this is part of the dynamic at work: the pitched battle and occasional accommodations between the 'orchestra' and the piano. It begins with a low hum to which, after a few minutes, Tilbury introduces the spare yet crystalline chords heíd perfected with AMM, very much out of Morton Feldman in one sense, but also very much his own. As MIMEO gathers strength, it changes form from a comfortable "nest" for the piano to an enveloping storm, flooding the sound-space with a nearly infinite range of sonorities, as chaotic and disciplined as a hurricane. The playing field would have been difficult enough as is, but Rowe threw yet another wrench into the proceedings by having pianist Cor Fuhler play inside the same piano as Tilbury with the motive of not allowing the latter to get into anything resembling a comfort zone. Fuhler tries to anticipate Tilbury's every move and acts to hinder it by damping the piano strings involved, clamping them down, etc. This forces Tilbury into areas that would otherwise have remained unvisited and adds yet another layer of conceptual complexity onto an already deeply rich endeavor. In this context, his playing takes on an almost Romantic quality, not just in the relatively melodic aspect of his approach but also in the heroic striving to achieve a balance against impossible odds. The multi-dimensional, thick conception and execution of the work allows for many repeated listenings that guarantee fresh discoveries each time, both in the actual sounds heard and, perhaps more importantly, in the relationships between musicians and, analogously, between past and present as represented by the two main factions here. The question has been asked: Where does improvised music go after AMM? This is one amazing answer. All Music Guide, Brian Olewnick

Details

Cat. number: erstwhile 021

Year: 2002