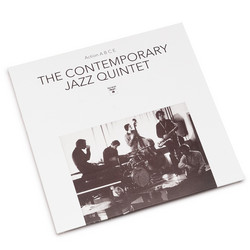

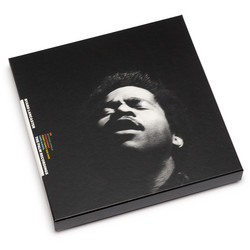

Mike Taylor

Trio, Quartet & Composer Revisited

Temporary Super Offer! When on January 20 1969 Mike Taylor was pulled from the River Thames – shoeless, alone, confused, ultimately drowned by his own hand – the young pianist and composer was only 31. A cynic might say that hindsight is a wonderful thing and that it was only years later, when fans began to speculate on the fatal glamour of an artist who died so young, that fellow musicians began to recollect him as a genius of modern music. At the time, they might well have thought of him – and been quite justified in so thinking – as a helpless, self-destructive eccentric, lost to drugs and delusions, hampered maybe by the thought (he had been a national service officer in the Royal Air Force) that he was just a little superior to everyone else. The evidence, though, is that fellow-musicians did recognise something special in Taylor, even if it was never fully achieved. His compositions were explored by the New Jazz Orchestra.

Colosseum made his “Jumping Off The Sun” a prog rock hit. Norma Winstone gave a haunting version of his “Song Of Love” on her Edge Of Time LP, one of the great jazz vocal albums ever. Had Taylor only known it, or cared, he was about to receive substantial royalties for his three songwriting credits on supergroup Cream’s Wheels Of Fire, a smash album of 1968. Those three songs, co-written with Ginger Baker, are included here. Quite what hand Taylor had in them isn’t clear now and certainly the recorded versions were probably quite distant from anything he had conceived. The truth is that Taylor thought of himself more as a composer than as a jazz pianist. His later eccentricities – walking around London with a small clay drum, living rough among the deer in Richmond Park – were part of a certain romantic detachment from the jazz community of the day. In person, he was perhaps more like the rockers, long-haired, inspired by LSD, disgusted by commercialism. While the Cream royalties worked through the system, Taylor sustained himself with odd jobs, mostly dishwashing, and borrowed funds. He had, before his sharp and sudden decline, made two records that stand as among the most important by a British musician of the time. They are Pendulum, of which a single track is abstracted here, and the magnificent Trio, which is reproduced in its entirety. It is an astonishing set, but its qualities are not just down to Taylor. His posthumous charisma has tended to obscure the contributions of drummer Jon Hiseman, and bassists Ron Rubin and Jack Bruce. It’s pleasingly characteristic of Taylor’s cross-grained approach to life that a trio album should involve four players, but in fact Bruce and Rubin (the latter was the pianist’s more loyal associate) only play together on the originals “Two Autumns” and “Guru”, and a remarkable extended version of “While My Lady Sleeps”.

Listening to it now, it’s hard not to make a connection with Bill Evans’ most famous recordings, and for similar reasons. It isn’t just what the piano is doing, it’s what is happening between piano, bass and drums. Now gone himself, but leaving an astonishing tape legacy behind him, Jon Hiseman is one of the most underrated drummers of recent times, sometimes accused of blurring everything to a rock scuffle, but constantly shifting time and metrical emphasis within that. Bruce was a bassist who often sounded as if he should be playing the cello, as indeed he once had and occasionally did in future. He plays alone on “Stella By Starlight”, leaving the devote

Rubin, with his resonant, Wilbur Ware-like sound the other three tracks. It was, apparently, a misunderstanding, rather than a conscious artistic decision, to have two bass players. Bruce admitted later that he’s misread his diary and turned up at the same time as Rubin, though unbooked.

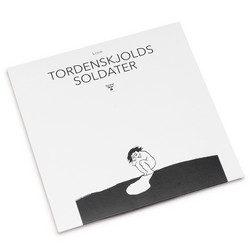

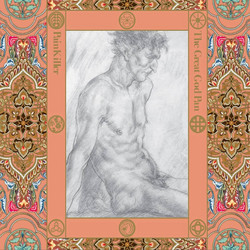

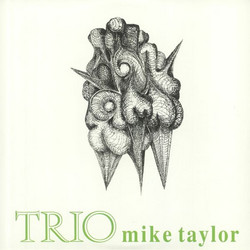

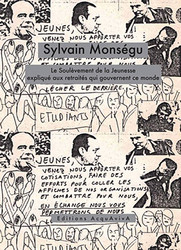

Consider the opening “All The Things You Are”, a more than usually complex standard, originally written by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II for the show Very Warm In May. Its 36 bar structure set it apart from the run of Broadway tunes, and while most jazz improvisers have preferred to focus on the chorus, it’s clear that Taylor knows the verse and understands the song’s subtle dramatic structure, not just its “changes”. The opening track on Trio, it conveys perfectly Taylor’s ability to invest a tune with an air of suspended drama, of a virus? – but it perfectly conveys Taylor’s sense of music as organic but deeply mysterious. The long version of “A Night In Tunisia” from the earlier Pendulum is arguably more conventional. The presence of a saxophone might seem like a normative element, but it’s more that Taylor hasn’t yet quite found the group dynamic that made Trio so remark-able. Compare it, though, with something like the long tracks on Krzysztof Komeda’s Astigmatic, recorded around the same time as Pendulum and it is clear that something distinct and separate was going on in European jazz at this time. European musicians responded more quickly and creatively to the challenge of rock and, though Taylor clearly had a foot in that camp – British music being much less compartmentalised than its American and continental equivalents – he was thinking how jazz some revelation that is constantly withheld. One takes the same impression from “The End Of A Love Affair” and “Stella By Starlight”, both of them familiar enough as jazz standards but again reinvested by Taylor with their original dramatic intent. The cover of Trio – designed by sculptor Jim Ritchie rather than the pianist himself, though Mike had a strong eye for visuals and often handcrafted his own scores – is a perfect metaphor for the music, a strange biomorphic form that seems to have one continuous surface wrapped in on itself. The covid pandemic has perhaps made us unusually susceptible to imagery of this sort – is it could accommodate to it and still maintain its integrity. The surrealism of Ginger Baker’s lyric on “Pressed Rat And Warthog” is typical of the time but its reference to “atonal apples, amplified heat” throws a sour glance at the dominant music of the day, the curiously doctrinaire values that Taylor quietly ignored. Sadly, his “three-legged sack” was never filled again. In January 1969, Mike “went straight round the corner and never came back”. - Brian Morton