We do require your explicit consent to save your cart and browsing history between visits. Read about cookies we use here.

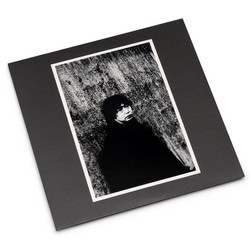

Based in Tokyo, Keiko Higuchi is a vocalist and instrumentalist internationally renowned both for her solo performances and extensive collaborations in the world of underground improvisation, jazz and the avant garde. On Vertical Language, Higuchi has created an evocative and hauntingly beautiful album that unfurls in equal parts light and darkness, form and emptiness. On solo voice and piano as well as in duets with bassist Louis Inage, Higuchi performs a collection of songs and improvisations that take unexpected paths; her voice and piano starkly, soulfully emerge. They gradually take form as sparse notes resonate and build into intense layers of sound. The music is unvarnished and deeply personal- it embraces traditional Japanese and spiritual musics as well as even jazz and bossa nova but never completely turning itself over to their familiar forms.

More than simply an album title “Vertical Language” refers to the distinctive musical approach that Higuchi has developed over the past twenty years. Her music is centered on the breathe and pulse- rather than set ‘horizontal’ musical rhythms or structures. It illuminates the connection between the artist’s body and sound. In her music piano chords and voice sound out in an instant and expand, floating off in new directions. The music embraces silence and negative space or the Japanese concept of “Ma” as well as the small ‘imperfections’ that any moment or sound might contain. Each moment in her music is as much imbued with what came before as what will come next - each note expands in space and can never be seen from just one perspective. In her music, Higuchi is constantly taking us to a place that neither she or we can quite yet see.

There is a 1998 episode of The Simpsons with a scene in which Lisa is watching an avant garde violinist in a jazz club. The punter next to her scoffs and says, “It sounds like she’s hitting a baby with a cat.” Lisa replies, “You have to listen to the notes she’s not playing,” to which he retorts, “I can do that at home.”

In this gag, the writers identify a thoroughgoing concern of avant garde music – the notion that silence is just as aesthetically significant as sound; that ostensible absence can be fecund or positively charged. The affinity of this concern with the Japanese concept of ma or negative space informs this new record by vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Keiko Higuchi, whose A side consists solely of her singing and piano playing while on the B side she is joined by Louis Inage on electric bass. This theme is perhaps surprising, because silence seems anathema to Higuchi’s most recent releases. Hoichi The Earless, her 2020 collaboration with Jacob Kirkegaard, Tobias Kirstein and Niels Lyhne Løkkegaard, sustains high-pitched drones for its 25 minute runtime. Last year’s Summoning Ancient Spirits was a duet with Manuel Knapp overwhelmed by the latter’s Pain Jerk-esque digital tornados of sound. And on Vertical Language she certainly does not have the restraint of, for instance, John Tilbury in her piano playing.

There is more silence here than on the aforementioned releases, but most tracks are grounded in recurrent melodic piano figures, which often build from delicately picked notes or sprightly couplets into resonant allegro passages, and only occasionally stray into atonality. This is accompanied by her accomplished free jazz vocalisations, and Inage’s impressionistic bass playing (whose precedence in the final track “Esashi Oiwake” seems to give Higuchi license for slightly more counterintuitive piano improvisations).

All of this ostensibly does not give much time over to negative space. Nevertheless, the album feels starkly spacious. While it distinctly lacks the shuffling ambience of a live record, it bears an immediacy which makes the listener feel as if they are in the room with Higuchi. It is perhaps in this sensation of positively charged shared space between the listener and performer that the album best manifests the notion of ma.

Keiko Higuchi must be one of the foremost proponents of the human voice as an instrument and Vertical Language is, among other things, a stunning showcase for the power and flexibility of her inimitable vocals. Higuchi’s work lives in the liminal spaces between the jazz, modern classical and avant-garde worlds, and as every track on this sometimes very bare and stark album demonstrates, the result is as difficult or as simple as you perceive it to be. Take the opening track, “Scenery One” for example. Eleven minutes long, it is in one sense minimalist, consisting of just the sparsest of piano chords and notes, reverberating in darkness, and Higuchi’s wordless vocal acrobatics. But there’s nothing minimalist about that voice, and it goes on for eleven minutes. Murmuring, soaring, it is at times extremely operatic, at others the epitome of jazz, it has a rare musical freedom and feels, for all its undoubted difficulty, deeply human and as natural as breathing. There’s no melody to speak of, or any kind of obvious structure; it just is, and for as long as it plays it suspends all in its timeless spell. Unless, of course, you are just irritated by it; which is also very possible. That possibility is heightened significantly with “Scenery Two,” which takes the same ingredients, voice and piano, but is far more strident, bluesy even, with Higuchi’s voice at times taking on an almost hectoring, irritable tone, mirrored by her piano playing, which becomes busy and frantic.

Towards the end of the piece, double-tracked vocals wail and drone and, as elsewhere on the record, the effect is both powerful and a little frustrating as it feels like Higuchi has something urgent to impart, but the piece feels too enclosed and opaque to offer any possible readings. “Scenery Three,” by contrast, is fragile and earthy, the piano mostly limited to an evocative three-note refrain, over which Higuchi stretches her voice to its limits, but quietly – crooning and almost croaking in long, stretched out passages over the piano. It’s a haunting and even disturbing three minutes, ending as enigmatically as it began and feeling again like a kind of gnomic musical code that the listener doesn’t have enough information to decipher. After the three “Scenery” pieces, the rest of the album consists of the five-part “The Still.” The first of these is voice only and begins almost like a mutated Gregorian chant, before taking us, it feels, on a journey down Higuchi’s throat as her voice is stretched to the point of coarseness, not so much soaring as coiling into strange and unfamiliar shapes. The second part of “The Still,” subtitled “Oseka” is far more palatable, but harsh and sinister too, its darkly reverberating piano surrounded by multiple voices, some singing almost conventionally, others almost forming words and ultimately declaiming in an extreme, ululating and throat-ripping way. It’s a little like Diamanda Galas in its flamboyant theatricality and unnervingly abandoned, alien quality. Unexpectedly, the third part of “The Still” is a version, sort of, of the old Spiritual “Motherless Child.”

The music – the piano joined this time by fluid and jazzy bass – is warm, fragmented and melancholy, but Higuchi’s extraordinary, love-it-or-hate-it vocal is the glue that holds the track together. She moans, intones and almost gibbers the words, using the song’s melody, more-or-less, but at the same time dismembering and taking it apart. It’s a bravura performance and, arguably cuts right to the bones of the song’s meaning, but also arguably, renders the whole thing ridiculous; you decide. The following “Black Orpheus” does the same for the venerable Luiz Bonfá song. It has the same warm, bluesy feel as “Motherless Child,” the piano and bass giving the track an immediate sense of structure which is initially undermined by Higuchi’s – presumably deliberately – definitely-flat singing. As she becomes more impassioned, the song picks up considerably and again is slightly reminiscent of Diamanda Galas in its strange and wavering intensity. The album’s finale, “The Still: Eashi Oiwake” is easier to digest, with the exploratory piano and bass up front and Higuchi’s strangely unravelling vocal mostly banished, atmospherically, to the background, this time evoking the otherworldly soaring voice of Yma Sumac. Its most extraordinary passage occurs towards the end, when Higuchi’s voice takes flight, only to end on a jazz/blues phrase rather than the expected operatic one.

Needless to say, Vertical Language will not be for everyone, and even while admiring its indisputable skill and originality it’s possible to identify a few passages where it seems to teeter on the edge of self-parody. That said, the power and flexibility of Keiko Higuchi’s voice is nothing short of stunning and it’s matched by her creativity as a musician and skill as an arranger. Vertical Language is the perfect title for this album, a collection of pieces that strip away and deconstruct the conventions of music and rewrite its rules from the ground up. And if, in the end it leaves you craving something more mainstream and melodic, then that is further testament to its utter uniqueness.

Related products

More by Keiko Higuchi

More from Black Editions

Recently viewed

Become a member

Join us by becoming a Soundohm member. Members receive a 10% discount and Free Shipping Worldwide, periodic special promotions and free items.

Apply hereSoundohm is an international online mailorder that maintains a large inventory of several thousands of titles, specialized in Electronic/Avantgarde music and Sound Art. In our easy-to-navigate website it is possible to find the latest editions and the reissues, highly collectible original items, and in addition rare, out-of-print and sometime impossible-to-find artists’ records, multiples and limited gallery editions. The website is designed to offer cross references and additional information on each title, as well as sound clips to appreciate the music before buying it.

Soundohm is a trademark of Nube S.r.l.